Hugs not Walls: Reuniting the Children by Mark D. Walker

A sign hanging in the Anapra neighborhood of Juárez, Mexico, translates to “Hugs Not Walls.” (Brittny Mejia / Los Angeles Times)

The separation of children from their families on the U.S. border has created one of the saddest and most contentious issues of an already complicated debate about immigration into the United States. The existing frenzied political debate and false narratives it generates make it difficult, if not impossible, to turn this crisis into an opportunity to better appreciate the trauma caused those children separated from their families, and the grassroots efforts to bring these families back together and deal with the negative impact of the experience.

Despite the trauma and pressures placed on immigrants, especially the children, a number of individuals and groups around the country have stepped forward to support the immigrant families and educate the public about their plight and why they deserve our respect and solidarity. The reasons they step out differ: religious beliefs and commitment, compassion, an understanding and appreciation of what immigrants mean to our community and more.

Who can forget the video of the children behind a metal fence sitting on the floor with only a metallic blanket to keep them warm in the winter cold? Who can ignore the children’s cries and sobs for “Mami,” and the guard’s pathetic response, taunting the children as being an orchestra of whiners, or the guards pulling small children out of one cell block and into another as they kick and scream, not knowing where their parents are or why these strangers are treating them so violently and with such disdain? Who can witness without empathy the agony of the mother whose son didn’t recognize her after three months of separation, and who wanted nothing to do with her, as he felt abandoned and betrayed?

The number of children separated from their families (2,700) was even more than initially stated, according to a report issued by the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services. This number included 118 separated children taken between July and early November—after the administration halted the family separation effort because it had provoked a political firestorm and public outrage. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, the total number of children separated from their families since July 2017 is more than 5,400. There are currently over 13,000 detained children–the largest population ever—a number that has increased more than five-fold since last year.

Although previous administrations also separated minors from adults at the border in some instances — usually when they suspected the child had been smuggled in, or the parent appeared to be unfit — the report documents a sharp increase in separations under President Trump. The actual number is still hazy, due to the poor quality of the federal tracking system.

They Just Took Them?

Juana Francisca Bonilla de Canjura wiped tears from her face in the courtroom as she listened to the proceedings through a translation headset. In her hands, she clutched the passports of her two daughters: Ingrid, 10, and Fatima, 12. They had come together from El Salvador, and then were separated at the border. The bright blue documents were her only way of getting them back.

“I don’t have any idea where they are,” she’d told a Washington Post reporter shortly before the hearing began. “Nobody knows anything. Nobody says anything — just lies. They said they were taking them for questioning, and we were only going to be apart for a moment. But they never came back. What pains me is the thought they are suffering without me,” she said. As she spoke, a Border Patrol agent in green fatigues cut off the conversation.

In a McAllen, Texas courthouse, 71 disheveled immigrants caught illegally crossing the Rio Grande filled the courtroom, the defendants’ shackles clanking as they sat down on wooden benches. The federal magistrate started proceedings with, “Good morning. We’re here to take up a number of criminal cases that allege that the defendants violated the immigration laws of the United States.” According to a report by Michael Miller in the Washington Post, federal courtrooms in Texas, and across the Southwest, are being flooded with distraught mothers and fathers who have been charged with misdemeanor illegal entry and separated from their children, a practice decried by many as traumatizing and inhumane. Last month, a Honduran father separated from his wife and 3-year-old son killed himself in a Texas jail cell.

Separation has more than psychological consequences, as no less than three Guatemalan children died when they were being processed through the overburdened government border control system, which often has inadequate medical staff. One Guatemalan girl, Jakelin Caal Maquin, who went into cardiac arrest from exposure during her grueling trip across the border, was taken to a local children’s hospital, but it was too late. Nothing is worse for a parent than one of their children being taken, never to return, and hundreds more were separated and have yet to be located and reunited with their families.

Sister Mary McCauley, who witnessed the impact of the largest federal immigration raid on a business at a chicken and beef processing plant in Postville, Iowa, told me of a sixteen-year-old boy who told one of the volunteers, “I didn’t come here to rob people or do bad things. I just came to work to earn money for my family. Why do people hate us so much?” An honest and timely question.

Although the administration seemed intent on making the overall experience as difficult as possible, they didn’t have the necessary infrastructure in place to deal with the influx of children. In Phoenix, they began dropping busloads of families off at designated churches despite their inability to absorb all the new arrivals. The numbers were so great that ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) agents began dropping them off at bus stations with no support, as church groups and local charities scrambled to respond to the large influx of unannounced immigrants.

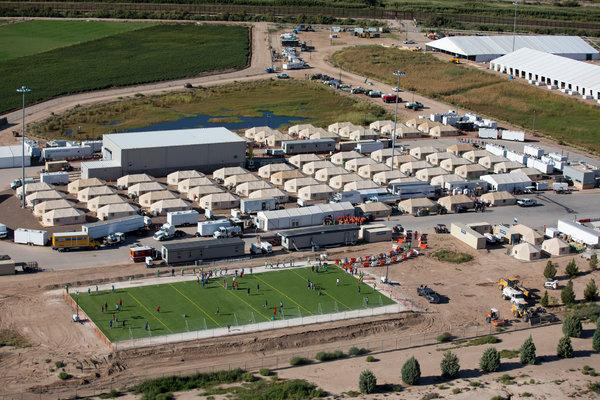

In a New York Times report, the number of detained migrant children has risen sharply since last summer. Over 1,600 migrant children have been sent, with little notice, on late-night voyages to a barren tent city in West Texas, where they do not receive schooling and have limited access to legal representation. These midnight voyages are playing out across the country, as the federal government struggles to find room for record numbers of detained immigrant children.

Advocates of the “Hugs” or “Abrazos”

Response

According to a Fast Company article by Gwen Moran, Julie Schwietert Collazo was listening to a radio interview in downtown Manhattan. The interview featured Yeni Gonzalez Garcia, a Guatemalan mother seeking asylum in the U.S. who was being held in immigrant detention in Arizona. Her daughter had been taken and placed in foster care in New York. According to her attorney, if she could post bail, she could relocate to New York and work to reunify with her daughter. So the only thing separating her from her daughter was money, in this case a $7,000 bond.

Julie thought, “Okay, that can’t be that difficult.” Julie and her husband had a number of friends who were concerned about the plight of families being separated at the border, so they set up a “Go Fund Me” page, which would be the catalyst for their new organization, Immigrant Families Together. They soon learned that Yeni would be unable to apply for authorization to work until her application had been processed, so this would be a long-term commitment.

This didn’t deter Julie, whose “Go Fund Me” effort raised $1 million, reuniting 60 families and providing support to roughly 100 families who were also going through the asylum process, helping with everything from legal counsel to locating a place for them to live. Julie’s success motivated others to raise funds to support asylum seekers, like a couple in Menlo Park, California. Already donors with the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services, a San Antonio, Texas, nonprofit focused on providing free and low-cost legal services, this couple decided to launch a Facebook fundraiser for the organization. It went on to generate $20 million, tripling the group’s annual budget and making it the largest fundraiser in Facebook history.

Others have responded to the immigration issue in a very different way from fundraising and financial support. Guatemalan-American filmmaker Luis Argueta has been telling immigrants’ stories for over ten years, to overcome the misperceptions and fears about the “invasion” of caravans from the Northern Triangle of Central America. His films have been instrumental in educating Americans and bringing people together with better understanding and compassion, and also providing concrete steps for his audiences to help newly arrived immigrants.

Although originally trained as an engineer, in the 1990s Argueta began to focus on filmmaking: “I went back to my roots and told the story of the people of Guatemala both in fiction and documentary films. Providing a better understanding of Guatemalans on a global platform.” Argueta’s career took a turn when he learned of the largest and most costly immigration raid carried out in the history of the U.S. Nine hundred heavily armed Federal Agents, supported by helicopters, state troopers and prison buses, converged on Agriprocessors, Inc., in Postville, Iowa, which was the largest kosher meat packing plant in the United States at that time. Of the 389 arrested, three out of four (293) were Guatemalans.

“What I thought would be a four-day fact-finding trip has turned into eight years,” Argueta told radio program KGOU’s “World Views” in 2016. But in fact, this was when Argueta galvanized around the issue of immigration.

What impressed Argueta most about the Postville raid was the response of the community, first in Postville, and then in other communities around this little town in northwestern Iowa. People gathered to support the immigrants that had been left behind after the raid, and to support the relatives of those immigrants who were in jail. It was remarkable. Argueta goes on to say, “This impressed me so much that I said, ‘The story needs to be told and it’s not going to happen in four days,’ so I stayed two weeks, and went back many more times. Twenty-nine totally. I began learning about the push factors that make people come to this country and decided I’d better go to Guatemala to see the communities from where they came.”

His experience in Postville has, so far, resulted in three documentaries about immigrants in Iowa and Minnesota and the small farm towns they call home.

“Something that struck me very much was how such a small Midwestern town could be such a microcosm of diversity,” Argueta said. He saw immigrants from all over the world, including Guatemala, Mexico, Somalia, Ukraine and Russia, all of whom call Postville home. Argueta later travelled to his native Guatemala to visit the communities where these migrants originated. He wanted to learn why people chose to leave their homeland, which provided him the ideal perspective of both ends of this epic journey.

A chance encounter inspired Argueta’s second film, Abrazos (2014), which tells the story of Abuelos y Nietos Juntos, a family reunification program. The film follows the journey of 14 U.S. citizen children from Worthington, Minnesota, who travel to Ixchiguan, in the Department of San Marcos, Guatemala, to meet their relatives, grandparents and even siblings for the first time.

Even though the number of children is small, they are a microcosm of the almost five million U.S. citizen children who live in mixed status families. Argueta reflected, “I think that we really must think about those children who are part of the future of this country when we think about immigrants because they live in constant fear that their parents might be deported. And I don’t think that any child should live with that fear.” Argueta goes on to say, “the film reflects the hopes, dreams and fears of these transnational families who, after being separated for nearly two decades, are able to embrace each other, share stories, strengthen traditions and begin to reconstruct their cultural identity.”

He told one group he was raising funds to make the project possible. “I am convinced that after watching Abrazos, you will find resonances with your own life and family history no matter where you come from. I also hope that you will consider getting involved in some way. Your support will be crucial to develop and carry out an outreach campaign in partnership with key organizations working in areas of child development, children’s rights and mental health. I hope you agree– their stories need to be told.”

Although the group did not sponsor any exchange trips after 2014, they discovered a need for transportation to the Immigration Court at Ft. Snelling, Minnesota, for those involved in the immigration process. This need was especially high with the large influx of children and youth, who came across the border in 2014-2015 seeking asylum. Not only can’t they drive, but the family members they stay with don’t generally have valid Minnesota driver’s licenses, so they are in need of transportation to their court appearances, which are a three-hour drive away. Consequently, the group set up a system of volunteer drivers to help with this need, and along with several other organizations in the Twin Cities, offered $25 gas cards to help them with travel expenses to their court appearances. One of the staff members accompanied them to court as well.

The last film of his trilogy, The U-Turn, (2017) tells the story of a group of immigrant women and children who broke their silence about the abuses committed against them at the Agriprocessors, Inc. plant. Thanks to the solidarity of the community that accompanied them, and to the U Visa program, their lives and the lives of those who walked along with them were transformed. The U Visa was established by Congress for victims of some crimes (in this case hiring illegal or underaged workers) who helped law enforcement investigate the criminal activity.

Argueta has become an expert on the complex issues of immigration in the U.S. He has shown films at multiple college campuses and led discussions after the viewings. He has participated in various panels on the subject and been honored due to his expertise. He recently presented screenings of The U-Turn at the University of Arizona in Tucson, as well as at Arizona State University in Tempe. After each presentation, he takes questions from any and all participants.

Margherita Tortora, Director at the New Haven Latin and Iberian Film Festival at Yale, said of Luis’s visit there, “He has worked tirelessly to educate people about the human rights abuses against his people through his documentaries. His work puts human faces and personal stories into the discussions about immigration in the United States. He is bringing down the wall! Thank you, Luis Argueta! I am looking forward to your presentation at the Yale Law School…”

Lessons Learned

Argueta shared more of his experience around immigration during a radio interview with host Suzette Grillot on KGOU’s “World Views” program in 2016:

Argueta: I also just came back from Guatemala from working on an advertising campaign for an agency in Washington that is aimed at stopping this phenomena (Caravans). This situation is not going to stop until we change the structural conditions of the sending communities. But this campaign is aimed to make people at least think twice about sending their kids. And so I have seen the phenomenon. It’s mind-boggling. However, we really must understand that until we address, in a very strong fashion, what is pushing people away as well as what is pulling them, we’re going to continue to have this phenomena.

Argueta: People know the risks of sending their kids but, when the families live lives that are full of risks every day, when the risk of a child becoming a member of a gang, or maybe not reaching age 15 because he or she is killed, they’re … sending them north–at least they have some hope. And they also see the results of others that have succeeded in this trip. It’s a terrible situation, the issues that immigrants have to face on a daily basis and that’s something that I wish on nobody. And they don’t do it lightly.

Interviewer Suzette Grillot: Issues like deportation and building of walls and, you know, increasing law enforcement on these issues. I mean how are some of the people that you’ve been working with, how is this going to affect the work that you do, first of all, and do you have any projects planned, and what is the response and reaction to some of the immigrants that you’re working with?

Argueta: Well, you know, one of the reasons I’ve been doing this for all these years is because I realize that often in the national conversation about immigration we get lost in the numbers. We talk about eleven million, quote unquote, illegals, and then we forget the human face of immigrants – and that is what my work aims to do, to bring out that human face, to make us realize that in every immigrant we do have another human being that is just like us. You know, “There, but for the grace of God, go I” means something that I have really come to feel very strongly. I had the privilege of going to meet Pope Francis two years ago and gave him a copy of my first two films and I said to him, “These are the stories of the immigrants that have touched my heart and changed my life. And that’s what I hope to do with these films, and with this conversation, because I go to universities, faith-based communities, and conferences, and engage in one-to-one or small group conversations with the hope that we will be able to recognize ourselves in the immigrants. At the same time, I think it is extremely important that we understand the root causes of the situation. This is not something new. This is not something that only happens in the U.S. It’s happening globally. So we must all really roll up our sleeves.”

Argueta: Also, on the other hand, realize that there are laws in this country that cannot change from one day to the next. There are things that the president can do with the stroke of a pen, but also there are a lot of other things that he alone cannot do and will need to change. You know, the support of Congress. So hopefully, our humanity will prevail and our common sense will prevail. This country needs immigrants. We cannot say we’re not going to stop. We’re not going to stop people from sending remittances to Mexico, Guatemala or El Salvador because those economies would collapse and it will backfire.

In June, Argueta was presented the Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award at the Peace Corps Connect Conference in Austin, Texas. The award is given to individuals who live in the country where they were influenced by a Peace Corps volunteer and where they promote the values of this organization. As part of the vetting process for the award, Argueta revealed that, “My experience with the Peace Corps taught me one of the valuable lessons of my life: to treat others as one would wish to be treated—the Golden Rule.”

Just prior to the awards ceremony, Argueta was screening Abrazos when the founder of “Abuelos y Nietos Juntos,” walked in with four of the children who had made the visit to their grandparents seven years earlier. They were now young adults and expressed their plans to attend college and pursue various professions. Several of them had returned to visit their families in Guatemala after the initial visit, and all four were in the front row to witness the presentation of the Global Citizen award to Argueta. During his acceptance speech, Argueta challenged the participants with, “At times like the present, when powerful winds of isolation and intolerance are blowing, it is more important than ever to speak out—to find our commonality as human beings, roll up our sleeves and to work to nurture the hope for peace in the world.”

More than a thousand of the children separated from their families have not been reunited, nor do their parents know where they are. Despite all the rhetoric about building walls, the number of undocumented migrants entering the country has reached a ten-year high. Eleven million undocumented immigrants are in limbo, some for over twenty years, and no integrated immigration reform is on the horizon.

And yet, the number of groups, the advocates like Julie and Luis, whose films are receiving more attention, not to mention the thousands who have given small gifts to cover legal fees, no matter what the final solution, they will continue to put the needs of the migrant children and their families’ well-being before the political bickering, hate talk and misinformation. All of these actions are a reason for hope.

Note from the editor: This article was first published in the Arizona Literary Magazine and was an essay winner in the Arizona Authors’ Association’s Annual Literary contest.

REVUE magazine by Mark D.Walker

About the author: Mark Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala, 1971-1973, working on fertilizer experiments with small farmers in the Highlands. Over the next 40 years, he managed or raised funds for many international groups, including Food for the Hungry and Make A Wish International and wrote about those experiences in Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond. He is also a contributing writer for the Revue magazine: Maya Gods & Monsters; The Making of the Kingdom of Mescal; Luis Argueta – Telling the stories of Guatemalan Immigrants; Luis Argueta: Guatemalan Filmmaker Recipient of a Global Citizen Award and Traveling in Tandem with a Chapina.

His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. Go to MillionMileWalker.com or write the author at Mark @MillionMileWalker.com