Health Care in Colonial Guatemala

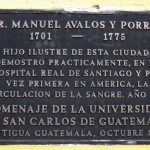

Part III: University of San Carlos Medical School

By the end of the 17th century, six hospitals had been founded in Guatemala. But, lacking scientific information and methods, hospitals provided little more than refuge or asylum. Sickness and cultural attitudes toward it were a social problem. In addition, the times were characterized by conflict between the king’s people and the municipality and constant struggles between those of conscience and those who enriched themselves with land acquisition, slavery and fraud. All of this kept the clamps on progress.

Before his death in 1563, Bishop Francisco Marroquín, a Franciscan, had made provisions in his will to found a school for sons of Spanish commoners and, in fact, a year earlier had laid the first stone, on property of the Santo Domingo monastery. He included the income from an 883-pig farm in Jocotenango to sustain the school. Marroquín’s admirable bequest would wait 58 years for fulfillment. The school, Colegio de Santo Tomás, was founded in 1620 and lasted less than 10 years due to trouble with funds. But in 1676 when Spanish King Charles II finally agreed to found a university in Guatemala, including a medical school, the selected site was of the then abandoned Colegio Santo Tomás. Marroquín would have been pleased; he had also left funds to found a university.

At the inauguration of the University of San Carlos in February 1681, according to Durán, “Pomp reigned in the streets and plazas.” But for all the ceremony, teachers for the medical school, promised from Mexico, never showed up. It came as no surprise. Several times during the history of Santiago de los Caballeros, Mexican doctors had been expected, even paid in advance, but didn’t come. “So scarce were doctors that it was impossible to find teachers for the new university medical school.”

Finally in October a degreed doctor arrived from Spain to head the department. But how discouraging it must have been for him to find empty classrooms! Given the history of doctors, the profession was not respected by the noble class and not preferred even by other social classes. “…nothing attracted as much attention from parents as priestly studies,” wrote Pardo, Castellanos and Muñoz.

A plague in 1686 wreaked havoc, and “doctors fled from the hospitals,” wrote Durán. A second doctor, Miguel Fernández, arrived from Spain and, having no students for 10 years, addressed himself to social and legal aspects of medicine. He insisted that good government requires healthy people, thus the right to demand compliance with laws. Administrators of hospitals were ordered to “not meddle in medical matters.” The brothers of the Order of San Juan de Dios, who notoriously wrote faulty prescriptions and to whose care had been entrusted administration of the hospitals, ignored the order. Fernández pled that those who offered cures without knowledge needed to be prevented if the people were ever to trust doctors. Without that, he added, there was little hope of attracting doctors to teach at the university. But the practice of medicine by those who had no right to do so continued, bringing a public declaration in 1703 that “prohibited the practice of medicine under pain of six years of exile.”

The first medical student graduated in 1703. Only one of the seven who graduated by 1725 took up the struggle for an honorable medical profession. Others “transformed their noble and useful profession into sterile arguments and hateful rivalries.” Their personal behavior didn’t help. Durán refers to the “sect of drunken doctors.” Even the brothers of the Order of San Juan de Dios “ate well and drank numerous cups of chocolate while the sick suffered hunger.”

There were no medical graduates in the next 25 years. The university building tumbled in the earthquake of 1751, and the university moved to new construction south of the cathedral in 1763. By 1773 there had been only five more medical graduates.

Just as the history of Santiago de los Caballeros, now La Antigua Guatemala, was born of catastrophe, so ended the colonial city and the first period of university medicine with the earthquakes of 1773. Plus, in the months that followed, an epidemic, believed to be typhoid, hit the town killing 4,000, “doing much more damage than the earthquake,” wrote Durán. Victims were buried by the hundreds. Church and civil authorities talked and talked to find a solution and formed the first public health board in Guatemala. But it was the archbishop, not doctors, who figured out the source of the disease. The workers had fled to the highlands after the earthquake and returned carrying the disease. It then spread rapidly in the hospitals, where patients slept together and ate from the same plate. In the end, the head of the medical school concluded that the epidemic was due to influence of the stars that unleashed sulfates in the water which, freed in the air, poisoned and coagulated the blood.

Provisional care was provided, funded by a tax on shopkeepers, for the sick who would remain in Santiago while churches and hospitals moved to the new capital to begin again. To the sadness of silence as people left Santiago was added the silence of death due to the epidemic.

History and legend are full of stories. As bumpy as the health care road was, progress came—slowly, but it came. It would be 16 years before another medical student graduated. Meanwhile the study of medicine was flourishing in Spain, with thousands of students. Nonetheless, in Guatemala, “Teaching of medicine was defective originally, lacking teachers and students, but the errors of ideas and methods were the same as those anywhere,” according to Durán. “At the end of the 18th century the University of Guatemala was parallel to modern teaching of that century in Europe.

“The University of San Carlos was outstanding, producing books, doing dissections and experiments, founding an anatomy museum…and doing blood transfusions 80 years before London.”

References:

- Durán, Las Ciencias Médicas en Guatemala

- Álvarez, Hospital de los Hermanos de San Juan de Dios

- Álvarez, Historia General de Guatemala, Vol. II

- Pardo, Castellanos, Muñoz, Guía de Antigua Guatemala

- López, Proyecciones Socioculturales en la América Hispano

The author thanks Dr. Johnny Long for assistance with this series.

photos: Jack Houston

Hi Joy

This is a really interesting article. Medical history is so fascinating and it’s fun to read about how things happened a hundred years ago and in different places.

I recently worked at The Washington Home which was called The Washington Home for the Incurables founded in 1888. In those days people donated bottles of whiskey, cakes of soap, pounds of sugar, rocking chairs etc. to help fund the place. They were the first facility to admit cancer patients, which at that time was thought to be contagious.

Do you know of hospice in Guatemala? I’m a hospice nurse and will be traveling to Guatemala soon. I’d love nothing more than to visit a hospice while I’m there.

Best regards,

Andrea Feeney