When Giants Roamed The Land

FIFTY THOUSAND YEARS AGO

We were in the middle of one of the Earth’s cool periods. Ice and snow covered much of the land. Massive glaciers grew to blanket vast expanses of South and North America. The highlands of Central America were a winter wonderland, where mastodon and megatherium frolicked.

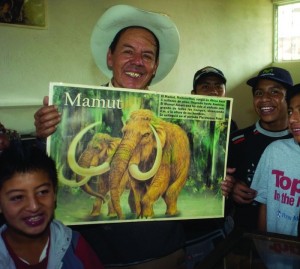

Octavio Alvarado (rt.) has become the enthusiastic caretaker of the

Chivacabé Mammoth site, near Huehuetenango, which now has a small museum.

So much water was locked up in the ice that the oceans were much lower and coastlines were not where they are today. This was especially true on the Caribbean side of the Mesoamerican isthmus, where coastal plains extended tens or even hundreds of miles beyond the present shoreline.

Changing climatic conditions caused many animal species from the Neotropical and Nearctic realms to converge on the isthmus, seeking more favorable weather. Vegetation had migrated, too. What had been highland temperate forests had moved down in elevation to become coastal pine-oak-liquid ambar groves. Thermophilic species had made their way south to equatorial regions. Worldwide a land area the size of modern Africa had emerged from the waves.

We think of Ice Age Europe as a tough landscape where cavemen struggled to survive, but the lower latitudes of our planet were quite pleasant. Humans, which had appeared on Earth millions of years previously, were busy going about their business of being fruitful and multiplying, exploring new territory, adventuring, learning to cultivate gardens, and gathering around campfires at night to gaze at the stars and be entertained by storytellers. Humans were few, nature was abundant, and skilled hunters and gatherers were able to provide plenty of nutritious food for their families.

THIRTY THOUSAND YEARS AGO

Explorers from eastern Asia, swept along by the Kuroshiro Current, managed to sail their rafts to the west coast of North, Central and South America. The land was rich and villages were established.

Some of these brave, adventurous seafarers continued to make their way across the South Pacific, colonizing the high volcanic islands as they went, and eventually returning to Southeast Asia in a circumnavigation of the entire Pacific Ocean.

Polynesians, whose territory comprises more than one-quarter of the planet, invented large, double-hulled catamarans, which could sail into the wind, allowing them to return and re-colonize South America. Little evidence remains to chronicle these early human endeavors simply because most settlements were built along coastlines that now lie beneath the waves.

The great west coast mountain ranges and deserts slowed both North and South American coastal colonist’s eastward migrations. Slowly but surely, over tens of thousands of years, our ancestors populated the continents.

THIRTY FIVE YEARS AGO

A dairy farmer by the name of Octavio Alvarado, who lives in the tiny village of Chivacabé on the outskirts of Huehuetenango, was excavating a well to get some water. The Alvarado farm is nestled in the Chivacabé Canyon, which drains into the Río Selegua of the Huehuetenango basin. To the north tower the Cuchumatanes mountains.

When don Octavio reached a depth of seven meters he encountered a strange, long and curved stone. As anybody who has ever dug a well knows, the worst thing that can happen is to encounter big rocks, which can even necessitate starting all over again in a different spot.

So our farmer was more concerned with the progress of his penetration than he was with the odd rock he had found. He struck the object with his pick and was relieved when it disintegrated rather easily. A few minutes later he hit another stone. This time he paid more attention to it because it looked just like a tooth—a molar, in fact —except that it weighed more than five pounds.

Don Octavio, a cowboy. since he was knee-high to a grasshopper, knew that he had found something extraordinary. No animal he could imagine could have a tooth that big. He took the object to municipal authorities who, unsurprisingly, paid little interest. But, as fate would have it, the secretary at the mayor’s office was aware of some Canadian archaeologists working in the area and sent Octavio in their direction.

Upon seeing the huge molar, the Canadians dropped what they were doing and accompanied Alvarado back to Chivacabé. Over the next few days numerous other mega-faunal remains were uncovered. The archaeologists explained to Alvarado that what he had found was the grave of a kind of huge, extinct elephant, cuvier’s gomphothere.

These huge mammals, three meters in height, looked like modern elephants, except for their spiral-shaped tusks. Naturally, this made the little village famous and everyone was happy with all the attention.

The next season a team of Canadian paleontologists arrived to conduct a proper scientific excavation. They uncovered not only the remains of other mammoths but those of giant ground sloths and giant armadillos (glyptotheium sp.), and even horses along with evidence of human presence at the site. This then provided one of the first proofs of human habitation in the region dating as far back as 15,000 years.

Everyone in Chivacabé was fascinated by the find and to know that long ago these prehistoric giants were roaming the land. Octavio Alvarado has become the enthusiastic caretaker of the site, which now has a small museum. He is available to guide visiting school groups and tourists and will be pleased to take you on a tour and tell you all about his giants.

Giant Ground Sloth Megalonchidae, these ancient relatives of our present day sloths, at full growth weighing in at five tons, 6 meters in length and able to reach as high as 17 feet (5.2m), were truly giants. (Courtesy of the Iowa Museum of Natural History, Univ. of Iowa)

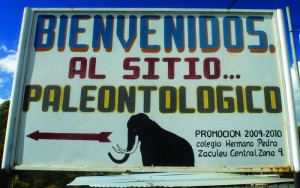

The Chivacabé Mammoth site is located just off the Inter-American Highway, six kilometers west from the provincial capital of Huhuetenango. The site is open to visitors every day and is free of charge; however, donations are gladly received.