Tschiffely’s Epic Equestrian Ride by Mark D. Walker

Tschiffely’s Epic Equestrian Ride: Over the Andes to Guatemala and On to Washington D.C.(Part of the Yin & Yang of Travel Series)

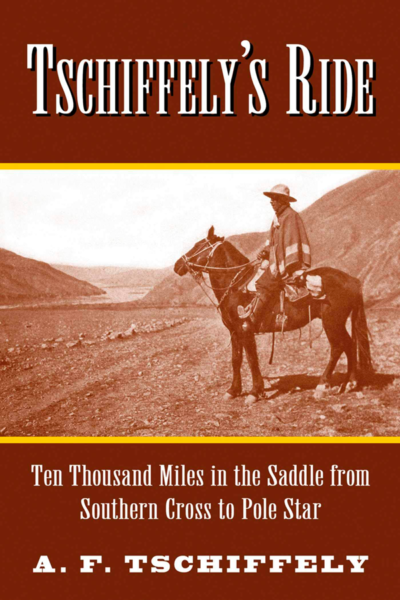

Tschiffely’s Ride tells the story of one of the greatest horse rides of all time. A.F. Tschiffely’s 10,000-mile journey through Latin America over a three-year period from 1925-1928, making him one of the most influential equestrian travel writers of his day.

My interest in his journey was piqued by my own 15,000-mile, eleven-country trip, going from Guatemala all the way to Southern Chile and back again, over a five-month period, 45 years after Tschiffely’s trip. He and I passed through many of the same out-of-the-way places. Further, my trip was also by land, my modes of transportation being bus, truck, train, and an occasional taxi, with one exception: a plane ride from Panama to Colombia (the author circumvented this portion of his trip in a ferry).

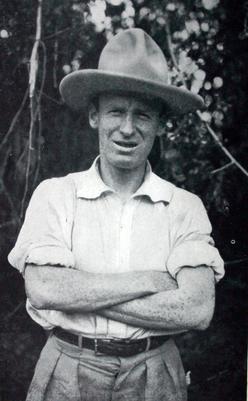

Tschiffely was thirty years old at the outset of his journey and had been the headmaster of a high school in Buenos Aires, Argentina for several years. As he explains in his book, although he enjoyed his work, he wanted a change, some variety and adventure: “I was young and fit; the idea of this journey had been in my ear for years, and finally I determined to make the attempt.”

Some of the newspapers in Buenos Aires deemed his announced trip as “impossible,” and “absurd,” yet he was not deterred. For his journey, Tschiffely decided on two Creole horses, descendants of horses brought to Argentina in 1535 by the founder of Buenos Aires, Don Pedro Mendoza. So, the fitness and resilience of his mounts were amply proven.

Almost as soon as Tschiffley headed north out of Buenos Aires, he started passing isolated communities, one of which was Santiago del Estero. There he realized that the dark thundercloud he saw coming his way was, in fact, an “invasion of locusts,” which formed a thick carpet–“every cactus plant and shrub was overhung with a grey mass…” –and was a portent of additional surprises and adventures to come.

One situation that he frequently encountered and which I can fully appreciate was trying to get directions from the local population, wherever: “It is no use asking these people the way, for they have only one answer and will invariably reply, ‘sige derecho no mas’ [just go straight ahead], although the trail may wind and twist though a regular labyrinth of deep canyons and valleys.”

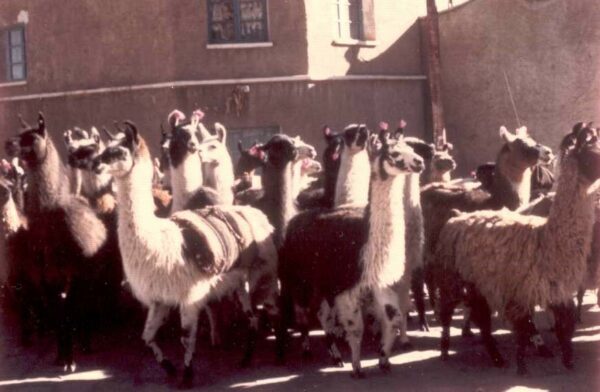

Eventually, Tschiffely and his two steeds would make their way to the Altiplano area of South America, and the silver-mining town of Potosi, Bolivia, one of the highest cities in the world. This portion of his book brought back personal memories of some serious altitude sickness at over 13,000 feet. The author often shared the local history of the places he visited, and, in this case, the horrors of early Spanish Colonial days. Their principal mine on the iconic Cerro Rico, was called Socabon and the Spanish coat of arms was carved into the rocks over the entrance where an “estimated 20,000 Indians were driven into the darkness of this mine, and none who entered there ever saw daylight again.”

Llamas, Potosi Bolivia:

Another situation that evoked personal memories occurred in the Andes Mountains around Ayacucho, Peru, where “Landslides and swollen rivers made it impossible to follow the road and compelled me to make a large detour over the mountains to the west.” In my case, 45 years later, another landslide in the same area forced me to make a long detour on my way to Chile, and on my return trip to Ayacucho, I learned that the same road had still not been cleared, almost three months and six countries later, resulting in “Plan C” in order to reach Lima.

The author’s detour was more harrowing, as he was forced to cross a “wild river” over a bridge which was “like a long, thin rope, wire and fibre held the rickety structure together. The floor was made of sticks laid crosswise and covered with some coarse fibre matting to give a foothold and to prevent slipping that would inevitably prove fatal.” This included walking across with his horses: “His weight shook the bridge so much that I had to catch hold of the wires on the sides to keep my balance…Once we started upwards after having crossed the middle, even the horse seemed to realize that we had passed the worst part, for now he began to hurry towards safety.”

As if this wasn’t dangerous enough, the author tells of a “mysterious disease” in Peru known as verruga, which is usually fatal, and manifests itself in great swellings or boils. “The local opinion varied as to its cause. Some said it was the water; others said it was in the air, while some blame insects.” Fortunately, both the author and his steeds were not struck down by this local malady.

Another situation I could identify with was crossing from Ecuador into Colombia over a natural bridge called Rumichaca [Quechua for Stone Bridge], where customs officers “wearing dirty clothes, stopped us and demanded to see my documents.” But this is where our experiences differed, as I was usually harassed and delayed by heavily armed, teenage guards looking for a bribe, but in Tschiffely’s case, “they had been advised of my arrival and treated me with courtesy.” Evidently, the author’s embassy did an excellent job of alerting local authorities of the author’s pending arrival and he was treated as an honored guest.

In Central America, Tschiffely spent significant time in Guatemala. One of the first places the author visited in Guatemala City was the famous relief map in Minerva Park, a place I have visited many times to get an idea where some of the isolated villages I worked in were located in relation to the rest of the country. “This map is made to a 1/10,000 scale horizontally and 1/2,000 vertically. It is made of concrete, and running water marks the rivers, lakes and oceans.” The nuance in Tschiffely’s case was: “On my way back [to his hotel], the streetcar derailed, and the driver asked me to help him lift it back on the rails.”

The author also encountered a darker side of Guatemalan history: “While in this city [Guatemala City] I saw a man who had been kept in a dungeon below the San Francisco church for sixteen years. This happened during Cabrera’s time. Food and water were lowered through a hole to the prisoners below, and those who died were hoisted out through the same opening.”

Fortunately, Tschiffely did not miss one of the more spectacular places in Guatemala, and possibly in all Latin America: “On reaching the summit of a high hill, after zigzagging higher and higher among the strong-smelling fir trees, I beheld, far below at our feet, Lake Atitlan. Its mirror-like surface of a deep blue reflected the surrounding mountains and the snow-white clouds that looked like huge airships. The lake is more than 4,500 feet above sea level, and rivals anything Switzerland has to offer.” Which he knew well, as he was born in Bern, Switzerland.

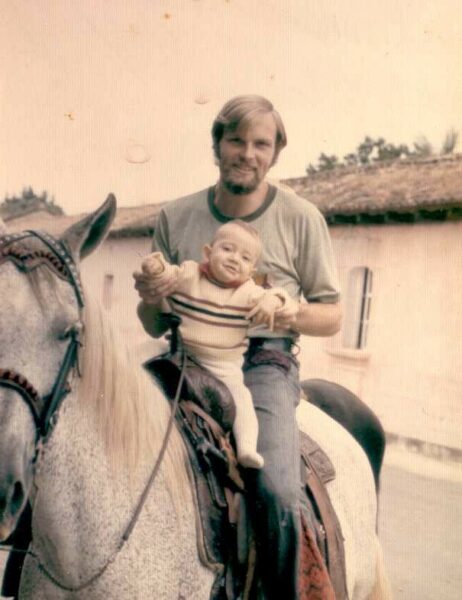

Volcanoes surround Lake Atitlan: I also rode horses not far from this lake 45 years later—on a coffee plantation on the Pacific side of one of the volcanoes next to the lake with my Guatemalan girlfriend, Ligia. Her grandfather owned a coffee plantation, San Francisco Miramar, on the slopes of Volcano Atitlan not far from Patulul. We visited the finca in the spring when the coffee plants were in full bloom and the aromatic smell wafted through the Cafetal. All very romantic at the time, and the horses were the best way of accessing some of the more isolated sections of the Cafetal where hundreds of seasonal pickers would soon be harvesting the lush, red beans.

Tschiffely, on the other hand, took a short-cut from Lake Atitlan further into the Maya highlands and visited a village well known for its distain for outsiders: “…this trail led over mountains and was rough in parts, and we had to pass through the village of Nahuala, which I had been warned to avoid. It is inhabited exclusively by Indians, who will not tolerate the presence of a white man overnight. In Guatemala, as in most Central American countries, the sale of liquor is a State monopoly, but the Indians of Nahuala pay the government a certain sum each year for not sending alcohol into their district.”

Tschiffley would be able to find places to stay for him and his trusty steeds on his trek through the highlands, as some of the better-off farmers had their own horses and would ride or walk them to their fields and walk them back, usually with some kind of harvest or firewood. The terrain was difficult, and the loads were heavy, making these working horses a very durable lot.

When I was in the Peace Corps, almost four decades after his trip, I needed a horse to access villages around San Jose Ojetenam, which was located deep in the highlands at 10,000 feet and from where I could see the two tallest points in Central America, the volcanoes of Tajamulco and Tacana. But this challenging terrain meant that the roads outside of town were impossible for vehicles to navigate much of the year.

I actually met my wife as she was riding a beautiful white horse through San Jeronimo, Baja Verapaz where she was spending the weekend at her father’s ranch. His favorite steed was “Zingaro,” a black Arabian horse that he taught to do the “Peruvian Paso” gait, which is an outward swinging leg action. When I finally returned from my five-month trek through Latin America, my wife and I headed to her father’s ranch several months later with our daughter, who rode around on my lap on one of her grandfather’s older, slower horses.

Tschifelley’s next destination, Mexico would be the most receptive country to the author, mostly because of his two mounts, Mancha and Gato, who he dedicates his book to: “Mexicans are born horsemen and lovers of adventure and the open air, and therefore, our journey appealed to them. Without meaning to boast, I just add that, as a nation, they are the ones who best understood the significance and valued the merit of my undertaking and showed their appreciation accordingly.

“Of all the banquets I have ever attended, the most brilliant and picturesque was given to me by the Asociacion Nacional de Charros [Charros are fancily-dressed Mexican cowboys]. It was appropriately given in the Don Quixote Hall in one of Mexico’s finest hotels. The diplomatic corps was well-represented, and all the participants who were charros wore the typical costumes of the different regions to which they belonged.”

Upon his departure from Mexico City, Tschiffely reflects: “To my surprise, crowds of mounted charros were assembled near the stables, ready to accompany me out of town for some ten miles, where, after many embraces and fervent handshakes, I sadly watched them disappear behind a cloud of dust.”

Tschiffely would continue his journey, to Washington D.C., where he was received by President Calvin Coolidge in the White House. Also, in D.C., he was honored by the National Geographic Society, which invited him to give a lecture.

After Tschiffely’s Ride, Tschiffely became a famous and successful author and moved to London, where he continued to write more books, one of which was a biography of his friend, Robert Cunninghame Graham, who wrote the preface for Tschiffely’s Ride. In 1937, the author returned to South America and made another journey, this time by car, to the southern tip of the continent, recording his experiences among the natives and the changes brought on by modernity in This Way Southward (1940).

His book, Tschiffely’s Ride includes an excellent map, which plots this epic journey, as well as various photographs. According to the New York Times: “It is pretty certain that the crafty Ulysses, Marco Polo, or the indomitable Drake would have been hard put to keep up with Tschiffely. This is a heroic book.” I was touched by this story and it brought back many fond memories of my own trek through Latin America which kicked off a life of travel and adventure.

About the author Mark D. Walker

(MillionMileWalker.com) stories are inspired by his Peace Corps experience in Guatemala and subsequent work over 45 years with innumerable International development organizations. Some stories are part of his award-winning memoir “Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond”. His articles have been featured in Ragazine, Literary Yard, Literary, Worldview, Quail BELL and Scarlet Leaf Review including one which was recognized by the Solas Literary Awards for Best Travel Writing. Some of his more than 60 book reviews are included in his column, “The Million Mile Walker Review: What We’re Reading and Why”, which is part of the “Arizona Authors Association” newsletter. All of his articles and reviews can be found at www.MillionMileWalker.com Mark is a contributing writer for the Revue Magazine. A revised version of this article was published in the February issue of Literary Traveler.

Go to MillionMileWalker.com or write the author at Mark @MillionMileWalker.com

REVUE magazine article by Mark D. Walker