Trouble in the Highlands

Poverty, population, drought and persistent repression

The influx of undocumented immigrants into the United States last year reached a 10-year high of more than 115,000 and has already passed that figure this year, according to the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol. Since the recession, Guatemalans represent the second-largest group of undocumented Latino immigrants after El Salvador, according to the Pew Research Center. No longer is the majority of these immigrant young males seeking work, but families and children, many of whom are seeking asylum.

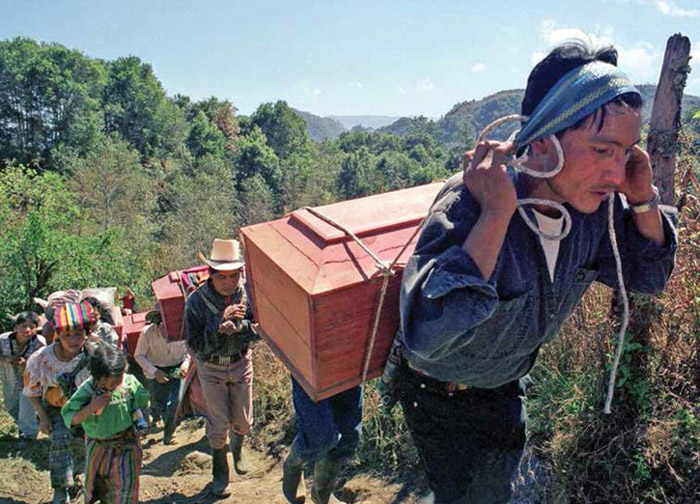

Ninety-nine bodies were exhumed in 2000 from a mass grave in Xolcuayl, Guatemala, 90 miles west of the capital city. A Mayan Quiche resident of this western highlands village carries the remains of a relative. Human rights groups claim a government military patrol was responsible for the 1982 massacre that occurred during a lengthy civil war in which 200,000 Guatemalans died.

So what is pushing these people away from their homes? What impact do our government’s policies and those of the Guatemalan government have on the process? And what lessons have we learned so that we, as citizens, and our government can deal with the situation?

The deplorable conditions of rural Guatemala have existed for hundreds of years. As a Peace Corps Volunteer in the western highlands in the 1970s, I received a jarring introduction to these conditions while hiking down the side of a mountain to one of my experimental agricultural plots. I passed by a small cemetery in the village of Calapte with a great many small graves.

One evening, the entire community was dancing and drinking, so I asked one of the teachers why.

“The villagers are celebrating the deaths of the angelitos,” he said, children who died before their first birthday. “They go directly to heaven because they haven’t committed any sins, so this is a happy time for us.”

I remember thinking, “but why so many?”

Over the years, I’ve returned to the Highlands with many international non-governmental organizations, only to find many of the same conditions and a deepened despair, especially in the departments where the majority of immigrants come from: Quiche, San Marcos, Huehuetenango, Totonicapán and Jutiapa.

I volunteered recently at a shelter church in downtown Phoenix and chatted with two Guatemalan immigrants, Hector and Felix, who had brought their wives and several children from the Guatemalan Highlands. Both were small-holder farmers forced to leave their land due to a protracted drought in the annual dry season or canicula.

This one lasted longer than usual, killing most of their crops, their basic source of food. Despite the risks, they believed the difficult move from Guatemala to the United States was worth it, compared to the seemingly hopeless situation they faced back home.

According to a recent New Yorker article on Guatemalan immigrants by Jonathan Blitzer, over 65 percent of the children suffer from malnutrition exacerbated by the drought, one of the highest malnutrition rates in the Western Hemisphere. The communities Hector and Felix come from are part of the expanding swath of Central America known as the dry corridor. It begins in Panama and snakes northwest through Costa Rica, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and parts of southern Mexico. As one Guatemalan climate scientist at the Universidad del Valle said, “Extreme poverty may be the primary reason people leave… but climate change is intensifying all the existing factors.” This phenomenon is underscored in a series of articles in the Guatemalan daily, La Prensa Libre, which reports that farmers just don’t know when to even plant crops to avoid these dry periods. The possible result is total loss of their harvests.

Felix told me his family left their home because he had to mortgage the land on which the family grew its food. “I’ll pay it off with the money I earn here.”

LIFE IN QUICHE

The Guatemalan government does work, but only for the two percent of the population who own 84 percent of the land, according to “The Agrarian Question in Guatemala” published by the nonprofit Food First in Berkeley. Most Guatemalans, especially the Maya population in the western highlands, are relegated to small, unproductive plots of land that force them to work for extended periods on large plantations on the South Coast or to look for jobs in the capital. This exploitation goes back to Spanish colonial rule when some Maya communities were forced to supply a “reparto,” sending a third of their male residents to labor in nine-month shifts on Spanish-owned plantations. This system of forced labor was supported by post-independence Guatemalan regimes throughout the 19th century.

I saw these conditions first-hand when visiting a coastal coffee plantation, where I recognized that the traditional garb of the worker families was the same worn by indigenous villagers working in the highlands. Conditions on the plantations are harsh and the pay low. In many plantations, these families will live for several months in lean-tos with limited, if any, sanitation.

Eventually these egregious inequities, combined with a population explosion starting in the 1950s, resulted in a period of violence lasting from 1960 to 1996, costing the lives of over 200,000 people, mostly from the Mayan population in the highlands. I led a Food for the Hungry donor tour to the Department of Quiche in 1995 and came across some pictures drawn by children in Chajul depicting planes dropping bombs and napalm on their homes.

I remember one visit with a small farmer whose child was being sponsored by a donor and when we entered their home, the first thing one of the donors asked was, “Where are the windows?”

Many of the homes we visited still had dirt floors, thatched roofs with no ventilation and few, if any, windows.

Quiche is the province suffering more assassinations and murders than almost any other in Latin America. In “The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop?” Guatemalan-American author Francisco Goldman presents testimony from a 1998 Recovery of Historical Memory Project compiled by the Catholic church on government/army abuses in places like Santa Maria Tzeja, Quiche: …The señora was pregnant. With a knife, they cut open her belly to pull out her little baby boy. And they killed them both. And the muchachitas (little girls) playing in the trees near the house, they cut off their little heads with machetes…

According to the Guatemalan Human Rights Commission, unbridled impunity still threatens the rule of law, including the failure to prosecute former President Efrain Montt and other high officials for hundreds of massacres and other human rights crimes committed during the 1960-1996 civil conflict. Frank La Rue, a longtime human rights activist in Guatemala and former United Nations official, told The New York Times in 2014, “You can only explain that (50,000 unaccompanied children fleeing north to the U.S. in 2014) when you have a state that doesn’t work.”

WASHINGTON’S IMPACT

In the early 1950s, the U.S.-based United Fruit Company, or “La Frutera,” exacerbated the unfair land distribution in Guatemala. The company owned over half a million acres of the country’s richest land but left 85 percent of it uncultivated. At the time the U.S. government appeared to consider the company’s interests the same as those of U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother, Allen Dulles, who was the Central Intelligence Agency director. Prior to the government service, the brothers had been partners in Sullivan & Cromwell, a law firm that represented United Fruit. The “secret” history of these two powerful siblings was brilliantly divulged in Stephen Kinzer’s “The Brothers.”

Smoke rises from graves in the San Marcos region of Guatemala after a 6.9-magnitude earthquake struck the nation in July, 2014. Human remains were exhumed from damaged coffins which were burned. The quake triggered landslides that blocked roads near the Mexican border.

In 1950, Jacobo Arbenz was elected president of Guatemala and began promoting social reform and land reform policies. United Fruit quickly rolled out a propaganda campaign that turned the U.S. government against the new regime and led to a U.S.-supported coup d’état in 1954. This abrupt change in government dealt a death blow to Guatemalan democracy and reinforced the inequitable land tenure system that kept the majority of Guatemalans on the margin of the larger economy.

The United States’ inability or lack of political will to control the proliferation of drugs within its borders has also impacted Guatemala by allowing drug cartels to gain ever-growing financial and political influence. In his 2011 New Yorker article, “A Murder Foretold,” David Grann wrote:

Overwhelmed by drug gangs, grinding poverty, social injustice, and an abundance of guns, it’s no wonder that violent crime rates have been sky-high. In 2009, fewer civilians were reported killed in the war zone of Iraq than were shot, stabbed, or beaten to death in Guatemala, and a staggering majority of homicides—97 percent—go unsolved.

A recent proliferation of “maras,” or gangs, began with the mass deportation of Latino criminals to Central America in the mid-1990s. The MS-13, for example, became an international gang that spread through the continental United States and Central America. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime reported in 2011 that Guatemala had the highest number of gang members in Central America, with 32,000.

The U.S. State Department rates the threat of violent crime in Guatemala as critical, and when I applied for a country director position for the Peace Corps several years ago, I learned that they’d moved their office out of Guatemala City and prohibited volunteers from even entering the city, due to security concerns. So, one can understand how centuries of political abuse, violence, and a depleted infrastructure that includes schoolhouses with no books and hospitals and clinics with no medications and often a lack of doctors, has created despair. This is why families continue to leave their homes looking for a safe haven and an opportunity to educate their children. It also explains why so many seek asylum, as opposed to simply looking for work. My years of visiting and working in Guatemala only confirm that the isolation and poverty facing many remote villages in the Highlands are similar to what I experienced 40 years ago.

HOW TO REDUCE MIGRATION

The United States encouraged civilian rule and elections in Guatemala in 1985, but subsequent elections in that country were deficient in terms of substantive democratic reforms. Latin America scholar Susanne Jonas, author of the 1991 book, “The Battle for Guatemala: Rebels, Death Squads and U.S. Power,” wrote:

“For the most part, from 1986 through 1995, civilian presidents allowed the army to rule from behind the scenes. After an initial decline, death-squad violence and other abuses by the army actually increased significantly in the late 1980s. Every regime since has been hampered by excessive influence from the military, human rights abuses and corruption.”

To address the causes of migration, the three Central American governments agreed to launch the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle with technical support from the Inter-American Development Bank and the U.S Agency for International Development. The program is designed to promote local economic, health and infrastructural support to the poorest provinces, which export the majority of refugees. But in April, the Trump Administration announced the U.S cut in aid the Northern Triangle countries, which includes Guatemala.

The plan was a step in the right direction, but its impact is likely to be limited by corruption, a continuing issue for Guatemala, which Transparency International says has one of the highest rates of perceived corruption in the world. Former President Alfonso Portillo was extradited to the United States in 2010 and charged with laundering $70 million in Guatemalan funds through U.S. banks. More recently, another former president, Otto Perez Molina, and a former vice president, Roxana Baldetti, were imprisoned in Guatemala for corruption as a result of efforts by Guatemala public prosecutors and the UN’s anticorruption commission, the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG).

The closest advisor to Guatemala’s current president, Jimmy Morales, the president’s brother, and the advisor’s son were arrested on corruption and money laundering charges in Jan. 2017. Eight months later, President Morales expelled Colombian Ivan Velasquez, the commissioner of the CICIG, when investigators began examining claims that Morales’ party took illegal donations from drug-traffickers. The CICIG also asked the Guatemalan Congress to strip Morales of his exemption from prosecution. The Congress refused, assuring continued impunity of Guatemala’s ruling class.

According to the Guatemalan Human Rights Commission, the Guatemalan Congress is considering a law that offers total amnesty to any officials involved in the abuses and massacres during the 36 years of civil conflict. Other abuses include death threats and killings of elected officials, witnesses, members of the judiciary, and others involved in investigations of government corruption and human rights crimes, including violent evictions, labor rights violations, and other human rights violations in the context of agrarian disputes involving thousands of rural families.

LESSONS LEARNED

At this point in our country’s history, we can choose to continue being part of the problem or offer effective solutions to the immigration issues challenging us. As U.S. citizens, we must appreciate that we are connected culturally, economically and politically to the people of Guatemala. Remittances from Guatemalans working in the U.S. reached $8.5 billion in 2019, according to a recent NPR report.

Our country’s foreign policy has always impacted Guatemala, and, unfortunately, as explained above, has contributed to the injustices there. More recently, our inability to limit the use of illegal drugs has much to do with the violence and poverty pushing large numbers of people out of Guatemala to the United States, as have macroeconomic conditions, climate change, corruption, and internal policies of the Guatemalan government.

The recent decision by the Trump Administration to cut all aid to Guatemala will exacerbate the situation. Luis Argueta, the Guatemalan American film documentary director NPCA recently named its 2019 Harris Wofford Global Citizen Award said a few months ago at Arizona State University that those who ignore the impact of existing U.S. government policies are “complicit” in perpetuating the ongoing influx of undocumented family members.

People escaping violence and abject poverty in Guatemala will continue to seek asylum and work in the United States, especially those with family ties here. Well over one million Guatemalans now living in the United States represent a lot of family members trying to reconnect. No wall, no matter how big, tall or wide will stop the ongoing influx of immigrants.

Instead of creating fear about an invasion of insurgents, we must educate ourselves and our neighbors about who these people are. We must treat them in a more humane manner when they arrive. And we should support the U.S. aid and international development efforts in the sending provinces so young Guatemalans can raise their families in their home countries.

REVUE magazine by Mark D.Walker

About the author: Mark Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala, 1971-1973, working on fertilizer experiments with small farmers in the Highlands. Over the next 40 years, he managed or raised funds for many international groups, including Food for the Hungry and Make A Wish International and wrote about those experiences in Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond. He is also a contributing writer for the Revue magazine: Maya Gods & Monsters; The Making of the Kingdom of Mescal; Luis Argueta – Telling the stories of Guatemalan Immigrants; Luis Argueta: Guatemalan Filmmaker Recipient of a Global Citizen Award and Traveling in Tandem with a Chapina.

His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. Go to MillionMileWalker.com or write the author at Mark @MillionMileWalker.com

Note from the editor: This article first appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of WorldView magazine by the National Peace Corps Association:

peacecorpsconnect.orgOur thanks and appreciation for permission to reprint.

I’m looking forward to the comments and thoughts from “Revue” readers on why they think so many Maya Guatemalans are fleeing their homes and heading north, what they learned from my article and what I might have missed.

Mark Walker’s comprehensive overview of conditions and historical precursors to the border crisis is a clear explanation of why US foreign policy must change to address the needs of developing countries like Guatemala. His article is a vivid, detailed depiction of why Guatemalans are leaving. Walker outlines how a coordinated multi-government aid program (with proper oversight) would provide the infrastructure needed for migrants living abroad to return to their farms and villages–or for those contemplating work abroad, making the decision to stay home.

Walker will continue addressing the underlying causes for the migrant crisis by taking on the Coordinating Producer role in the upcoming documentary on Guatemala and US foreign policy, currently in pre-production.

For information on the documentary, “Guatemala”, contact: halrifken@gmail.com

People forget that the US destabilized Guatemala and contributed to the immigration problem we see now.

Thanks Hal for the good overview and the reminder of the documentary we’re working on.

Geri–I mention the US destabilization of the US in both this article and in my book, “Different Latitudes”–a sad part of our foreign policy whose consequences we’re seeing today.