Protecting the Past for the Future

Threatened by years of abuse and neglect, the Mirador Basin needs help and it needs it now.

The 400-year sliver of history between the biblical Old and New Testaments, sometimes erroneously called the ‘silent years’, packed Planet Earth with progress. Alexander the Great studied at the feet of Aristotle and, zealous to unite the world under Greek culture, conquered his way east and then south through Palestine to found Alexandria in Egypt before his death at age 33 in 323 B.C. Meanwhile, Persian culture was spreading, and the Roman Empire was revving up.

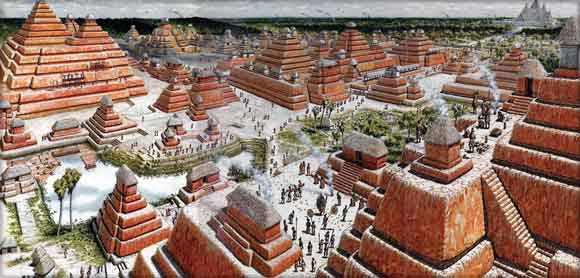

On the other side of the world, the ancient Maya were doing urban development with monuments and buildings more than 200 feet high sporting ornately carved façades. They studied science like the Greeks, built pyramids on a par with the Egyptians and roads like the Romans, to last 1,000 years. They moved construction materials and a rich economy of corn, squash, beans and cacao over a network of causeways within 820 square miles now known as the Mirador Basin. “They were an agricultural superpower,” says Dr. Richard Hansen.

As an archeology student in 1978, Hansen was invited by Catholic University of Washington and Brigham Young University to join investigations for the next five years at the metropolis of El Mirador in the Mirador Basin, about 50 miles north of Tikal and 1,000 years older. Hansen then did further investigations sponsored by the Guatemalan government and so has studied the area for some 30 years.

“We’ve mapped and excavated 51 cities that were home to perhaps a million Maya in the basin, with the largest known Mayan structures in size and scale.” A small sample of script, found chiseled in stone, may represent the earliest writing of the Maya world. The causeways measured up to 130 feet wide, 13 feet high, “…and they were paved!” Hansen adds.

Ongoing archeological excavations may reveal much more. The cities of the Mirador Basin were abandoned about 150 A.D., although modest resettlement began 600 years later. Jaguars, monkeys, crocodiles, turtles and birds with dazzling feathers still live there.

A Senior Scientist at Idaho State University, Hansen also directs the Mirador Basin Project, with a multi-discipline, archeological and environmental team representing 52 universities and research institutions all over the world.

“They moved a rich economy of corn, squash, beans and cacao over a network of causeways within 820 square miles now known as the Mirador Basin. They were an agricultural superpower,” says Dr. Richard Hansen.

The Mirador Basin, defined by hills on three sides, sits on an elevated plateau in the rainforest that crosses the northernmost border of Guatemala into Mexico. It’s a triangular, tropical wilderness complex within the block of land known as the Petén that juts up north into Mexico, “an ecological, biological and cultural system,” explains Hansen, reducing a complicated subject to simple terms.

The basin, estimated to be 60 million years old, has been threatened in the past few years by neglect and abuse, primarily from looting, poaching, logging and fires. Loss by logging has increased dramatically, the trees cut and the fields burned, then used for farming. Previous forests now are pastures.

“The swamps were crucial to the ancient civilization. They gave them the agricultural clout to become an economic superpower. But a magnificent society collapsed due to abuse of the environment. If you don’t protect the system, you lose everything. What we’re trying to do now is to save this thing.”

How? For starters, lease vs. log, i.e. pay rent as an alternative to logging to the people who claim the land. The long-range plan is to switch to tourism. “There are no villages in the basin, so no one would have to be displaced.”

“We’re training for tourism,” he says, referring to educational projects underway in adjacent communities that include ecology, health, literacy, reforestation, artisans and financial management. Locals already work together with the Mirador Basin Project teams. Development via tourist infrastructure would provide jobs and diffuse economic resources to population sectors while protecting the ecological integrity of the tropical forest and supporting scientific study and preservation of archeological sites.

Hansen adds, “The real danger to the area would be roads,” which could invite undesirable traffic and intrusion of all kinds. He envisions a roadless wilderness with a small train, “like a kiddie train”, to carry tourists for four to five hours from the southwestern edge of the basin to El Mirador, getting off and on to look at the ancient cities. He also envisions a five-star eco-lodge developed by Guatemalan entrepreneurs. “Why not?” For now, options to visit include hiring a helicopter or taking a three-day hike on an ancient causeway from Carmelita, where everything needed, including guides, mules, tents, hammocks, even cooks, can be rented. Nearly 3,000 people a year are hiking into the area.

It’s an enormous dream. The Project works with the Guatemala government, private foundations and alliances with an impressive list of Guatemala industries who share the dream; and funding, of course, is crucial to making it happen. It’s not a cash cow yet. But, as National Geographic summed it up in October, 1989, “Doing nothing will be far more costly.”

Could El Mirador be Guatemala’s Machu Picchu? It has been a century since that discovery, and today a well-oiled, integrated Peruvian system brings half a million visitors a year, while strictly staying green. Time is of the essence. “This is the last gasp,” says Hansen. “If we fail, we lose the whole basin. I want to preserve it for the future.”

Photos by © FARES Foundation (except as otherwise noted) used by permission.

Dr. Hansen will present the Mirador Basin Project during the World Mayan Archeology Convention at Casa Convento Concepción, La Antigua, June 18-20. (see page 62)

The Mirador Basin Museum, 15 avenida 18-01, zona 6, interior Finca La Pedrera, is open Mon-Fri, 9-4; free. 2289-3985. Also see: www.miradorbasin.com, www.fares-foundation.org, www.pacunam.org

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

Thanks to New Media/Universidad Francisco Marroquín for sharing this video with us.

- Dr. Hansen with mask on excavated structure

- Dr. Richard Hansen, Mirador Basin Project director, discusses location of the region

- Archeological work in progress at El Mirador

- Artists’s composite rendition of El Mirador, 300 B.C.-150 A.D. (National Geographic)

- Wild turkeys are commonly seen at El Mirador

- The devastation of deforestation in the basin

- Temple now excavated and stabilized

- Triangular-shaped area crossing the Guatemala-Mexico border geographically defines the Mirador Basin (NASA, National Geographic)

Joy, Thank you for another great report on the history of the area.