My Saddest Pleasures: 50 Years on the Road – First Stop, Guatemala

Part of the Yin and Yang of Travel Series by Mark D. Walker

Guatemala: First Stop on my Global Sojourn

(Trekking in the Peace Corps)

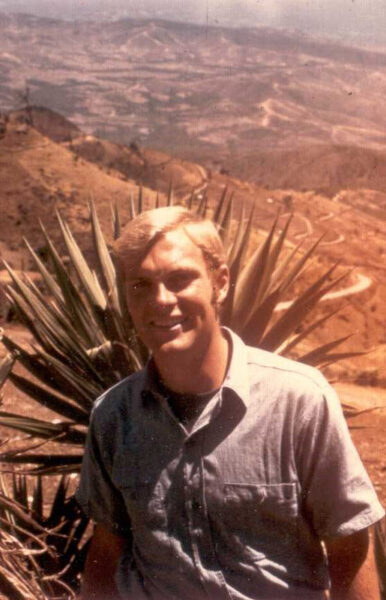

My global travels started at twenty-one years of age in Ponce, on the lush tropical island of Puerto Rico, where, in 1971, the Peace Corps sent me to learn Spanish, live with a local family and work, in preparation for my service as a volunteer in Guatemala. In Ponce, I was placed in a comfortable middle-class family with another Peace Corps Volunteer who already understood Spanish. Instead of counting myself lucky, I complained to my trainers that I hadn’t joined the Peace Corps to live in a comfortable home. Within a few days, I was shipped off to one of the toughest barrios in the city, Punto Bravo.

Initially, I felt isolated since I didn’t even speak rudimentary Spanish, but my neighbors soon introduced me to the entire lexicon of dirty words—profanity would become my linguistic specialty. I learned to pick up the local population’s foul words and the innumerable slang terms they used to communicate, e.g., Miercoles could mean “Wednesday” in one country and “shit” in another. This would become especially helpful in Guatemala, where the modismos (expressions) are a rich mixture of Spanish, English, and Mayan dialects. The villagers were always impressed that a gringo could learn their unique slang.

Christmas arrived after only a few months of training, and I turned down an invitation from the host family of another volunteer to join them on their yacht destined for Saint Thomas. Most reasonable volunteers would jump at any opportunity to relax on exotic Caribbean Island beaches. Still, I turned it down to experience the holiday in the barrio and to continue learning Spanish (or a facsimile of it).

I participated in the traditional processions celebrating the holy pilgrimage to Bethlehem by walking from house to small house and singing traditional songs with guitar accompaniment. I didn’t understand the lyrics, but I knew what Christmas was, so I caught on quickly. Traditional food included Lechon (pork stuffed with rice and cooked underground until the meat falls off the bones). Together with red beans, this would become my favorite local dish. Also, the families we visited offered local liquor. Although my memories are fuzzy, I remember having a good old time, and my appreciation of salsa and Caribbean music has stuck with me.

My next stop was Liberia, Costa Rica, in the state of Guanacaste in the northern part of the country, where I’d begin agricultural training and continue language training. I enjoyed these tropical wonderlands and looked forward to reaching my ultimate destination, Guatemala, The Land of Eternal Spring, with an average temperature of 75 degrees. Who could ask for anything more?

I chose an isolated work site in Guatemala to avoid English speakers (and Spanish speakers, it turned out). I brought a good array of short-sleeved cotton shirts, so I was surprised when my bus ride upcountry from the capital passed large herds of grazing sheep next to broad, sweeping wheat fields, and the dropping temperatures could only be called “brisk.”

When we arrived in Quetzaltenango, the Mayan highlands capital, at 7,600 feet, I realized that this part of the country was anything but tropical. I purchased a few sweaters at the local market while changing buses. Late that afternoon and several “chicken buses” later, I arrived in Ixchiguán, located close to the Mexican border on a 10,000-foot plateau, making it the highest town in Central America. It was surrounded by strangely-shaped mountains and hills, with streams that meandered through alpine forests and tundra-like “quasi-páramo” grasslands.

The surrounding area looked like a moonscape: barren, rocky, and inhospitable to any form of life. The mountains were part of the Cuchumatanes, which, in turn, were part of the Sierra Madres. This volcanic mountain range included some of the isthmus’s highest volcanoes, Tacaná and Tajumulco, at 13,320 feet and 13,845 feet. Not precisely the tropical wonderland I was expecting! Months later, I’d learn that the Peace Corps Volunteer who did the “site survey” had never actually visited the community, so it was a case of the blind leading the blind.

Upon disembarking from the bus in Ixchiguán, I entered a community enveloped in a thick, cold mist. After asking around, I figured out where the municipal building was and found several low-level officials who didn’t seem to expect me at all—or maybe they didn’t understand my broken, pathetic Spanish since Mam was their first language. Eventually, I confirmed that nobody had been informed of my arrival or the nature of the work I was to do (fertilizer experiments).

The officials showed me to a room down the hall, where I spent the next five nights—freezing. The room had a flimsy cot but no windows, no electricity, and heat source other than a few candles I had for light. The frame around the entry door was filled with holes, which provided an effective, though superfluous, air ventilation system. I learned that Guatemala is much more than a “tropical” country and culturally and linguistically more diverse than I could imagine. I also realized I’d have a lot of work to do before I could function effectively and help anyone.

Eventually, I’d move several hours to the south of Ixchiguán to live and work in the village of Calapté, which was at a lower altitude, warmer, and where the locals wore European-style clothes and spoke Spanish. One morning after my first year as a volunteer, I awoke with a horrendous stomach cramp. I was sweating profusely and only semiconscious. I didn’t have the strength to get out of bed, let alone walk the forty-five minutes uphill to the only daily bus that passed by. Peace Corps staff had previously assured me that if I ever got ill or had an accident, I’d be medevacked in a helicopter, which sounded good at the time. However, lying very sick in my bed, I remembered that the local telegraph system was down, and the only phone in the community didn’t work. I was up the proverbial creek.

Fortunately, when I didn’t turn up for breakfast, Doña Martha, who was like a second mother, came looking for me with two friends and found me in bed in a daze. They gave me a series of herbal drinks and the indigenous wisdom of these three women saved my life. Within three days, I was hiking up the hill to catch the bus to the Peace Corps headquarters in Guatemala City.

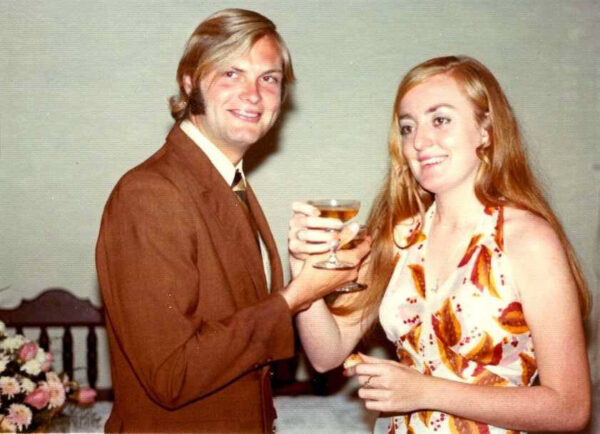

My medical condition was too risky to allow me to remain in such a remote village, so the Peace Corps staff sent me to San Jeronimo, Baja Verapaz, closer to more reliable communication systems and potential evacuation roads. Shortly after my arrival, my eyes locked onto a strawberry blond girl who, it turned out, was visiting her father’s small horse ranch nearby.

I was smitten at first sight, but like a dumb gringo, I wasn’t sure how to proceed with this pretty girl. Luckily, a Guatemalan friend from my new village made the introduction. Her name was Ligia, and she agreed to have coffee with me, and the rest is history, as they say. So, these initial trials and tribulations, plus the horrendous stomach pains and the amoebas that caused them, ironically and serendipitously led me to the love of my life.

Taking Donors to the Far Reaches of the World

Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.

—Mark Twain, The Innocents Abroad

By my early 40s, I had been a senior director for several international development agencies. It was my job to engage top and potential top donors and offer them an opportunity to see first-hand the work they supported. As a Senior Director of Fundraising for World Neighbors, a Christian-based, grassroots development agency with headquarters in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, donor tours were essential for our major donor strategy. Over the years, I led groups in several programs of World Neighbors, Food for the Hungry, and MAP International throughout Latin America and Asia.

The five stories that follow reflect how the beguiling randomness, disappointments, and challenges of travel in remote, far-off places can affect everyone and are a study on how to avert potential travel disasters.

Donor trips are a very tricky business. My primary focus always was on the donors. Still, I also had to negotiate and work effectively with local field staff, whose responsibility was the communities they supported and, to a large degree, protected. Their job was to strengthen the local group’s capabilities to solve problems and determine the future of their communities, while my goal was to engage critical donors and offer them an opportunity to meet the field staff so that they not only understood the work but also supported the activities that most motivated them.

Another challenge in bringing donors to overseas work sites is keeping everyone healthy when almost any local water or food can lead to severe intestinal problems. Some local ailments, like amoebas or malaria, can have long-lasting health implications. Yet, in protecting your donors, you had to do so without insulting local hosts. Overall, donor tours are worth the effort, as these trips impact the worldview and future giving of the participants, although leading them is not for the faint of heart.

Introducing Donors to the Highlands of Guatemala

In my late 40s as a senior director of Food for the Hungry (FHI), I led several groups of child sponsors, plus their children in some cases, and Foundation board members, to the Departments Quiché and Alta Verapaz in Guatemala. Twenty years before these tours, I had helped set up a local indigenous foundation in San Andres Sajcabaja in Quiché, so I knew the area had some of the most horrendous roads winding through the Cuchumatanes mountains.

Large trucks hauled loads of workers to the south coast during the rainy season to harvest coffee. They would put chains on the back four tires to enhance traction, but the chains and the weight of the trucks destroyed the roads. I also knew the health dangers Involved in traveling to this part of Guatemala. We almost lost our middle daughter after she contracted amoebas while living with us on a project farm I had helped establish.

Since the 1980s, the area was also the center of thirteen years of violence, with the local Ixil-speaking indigenous population caught between leftist guerrillas and right-wing death squads. Some 15,000 had been killed and thousands more displaced. I came across drawings of FHI-sponsored children, which depicted helicopters and planes dropping napalm and bombs on their communities. This happened, and it traumatized the local population, especially children.

This was not an area for the casual tourist, but FHI’s programs were excellent, and we were all impressed by the dedication of the staff who coordinated our visits. At no point did we ever feel that we might be in danger. After many years of doing this, I understood the importance of including children on these tours, as they represented the next generation of philanthropists. Also, many parents wanted to expose their children to how others lived around the world.

So, in March of 1997, I took Bill Williams and two of his daughters, fifteen-year-old Sarah and eight-year-old Emily, to Guatemala. My associate, John Scola, also invited John and Jeanette Tornquist from Illinois, generous and committed supporters. We flew on two small Cessna planes from Guatemala City to Santa Maria Nebaj in the Ixil Triangle of the Department of Quiché.

A Hunger Corps volunteer, Jodi Johnson, provided a program overview when we arrived. The Hunger Corps was like a Christian Peace Corps organized by FHI. Volunteers made a two-year commitment. After Jodi’s program overview and visits to water projects close by, it had clouded over, and I realized the two planes would not be returning due to inclement weather, a frequent occurrence.

I often traveled in small planes to the San Andres Sacatepequez area when I worked there years before, and sometimes I had to wait over a week until the clouds parted long enough for the pilots to return. But this timeline wouldn’t work for donors who have other plans, so I worked with our local staff to identify other transportation options and finally commandeered an old “chicken” bus (a former school bus painted with local scenes) and a driver and our little band headed out over a dusty, bumpy road from Nebaj through Uspantan, next to the Chixoy River, and eventually to our destination, Cobán, the departmental capital of Alta Verapaz. We had to leave the windows down because the bus had no air conditioning, allowing a steady stream of dust to enter. Seven hours later, covered in a fine layer of dust, shaken up, and in a daze, we finally reached Cobán.

After a quick orientation in Cobán from Patricia Cuba, the Country Director for FHI, we headed out in Land Cruisers to the community of Chiguorrán, where FHI supported a local school program. Classes there were taught in the Mayan language of Poqomchi’. During recess, little Emily distributed balloons and played with the students all about her age. Then the Tornquists and Emily showed the children how to blow bubbles. They all were laughing and having a good time together. The language barrier didn’t seem to be an issue.

FHI pairs up a U.S. sponsor, who pays about $21 a month to provide support such as education and food to a child in a program country equivalent to Guatemala. The Williamses’ encounter with the child they sponsored, Carmela, was the trip’s highlight. We hiked out twenty minutes from the vehicle to Carmela’s house, which was traditional for the area: a thatch-roofed kitchen in the back and a wood plank dwelling in the front. Firewood was piled up on the front porch. Several coffee and fruit trees, including bananas, surrounded the house. The animals, some chickens, and a few piglets were kept behind the kitchen area. The house had a cement floor and plastic sheets separated the interior into rooms.

Initially, Carmela’s parents couldn’t find her because she was hiding in the cornfield until the foreigners (us) left. When her father finally brought her to us, she wore a simple white blouse and a blue skirt, with plastic sandals on her feet. She was shorter than Emily’s shoulder, although she was probably the same age. I took a picture of Bill with the two girls and another with Carmela and her sister. I didn’t see any windows in their house, which would explain why it seemed so dark inside, even during the day.

Carmela’s father showed us around, and then we all sat on the front porch, and Sarah and Emily began asking questions about how they lived: What do you grow? Why doesn’t the kitchen have a chimney? How does Carmela get to school? (Walking 1 ½ hour per day). Where will Carmela go after she graduates from the local school? What do you eat for dinner? Where’s the bathroom? What was the round white structure in the back? (The girls were able to see the traditional steam bath that uses hot rocks and water to clean off, like our shower.) Carmela and her father responded to these questions and asked a few of their own, like where did Sarah and Emily live? Eventually, we had to say our goodbyes, and we brought the Williamses back to Cobán.

Despite the change in flight plans, rough roads, and cloudy, very long days, everyone in the group did fine. They had seen an isolated part of the country, which wasn’t that different from other parts of Guatemala, and they had met a local family up close and personal. None would be the same after this experience, and the Williams children would later become serious philanthropists, just like their daddy. Regarding Carmela, that’s more difficult to say, as the sponsorship program discontinues when the children graduate from primary school, so FHI often loses track of their whereabouts.

Obviously, after fifty years on the road, much of it in and around Guatemala, I was still capable of some real travel gaffes. And yet, we’re almost at our best and learn the most when we miscalculate and have to depend on the locals (and our wits) to figure a way out of the mess. And Theroux’s quip proved so true, “Travel is the saddest of pleasures as it gave me eyes,” no matter one’s age. And yes, Moritz Thomsen was right, “life is a bitch and then you die,” but neither of us would have had it any other way.

(MillionMileWalker.com) Mark Walker was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Guatemala,1971-1973, working on fertilizer experiments with small farmers in the Highlands.

Over the next 40 years, he managed or raised funds for many international groups, including Food for the Hungry, Make-A-Wish International, and as CEO of Hagar USA. He wrote about those experiences in Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond. He is a contributing writer for Literary Traveler and Revue Magazine: Uncovering the Art of Francisco Goldman, Tschiffely’s Epic Equestrian Ride; The Future of the Peace Corps in Guatemala; Maya Gods & Monsters; The Making of the Kingdom of Mescal; Luis Argueta – Telling the stories of Guatemalan Immigrants; Luis Argueta: Guatemalan Filmmaker, Recipient of a Global Citizen Award; Traveling in Tandem with a Chapina; Victor Montejo’s Dream of a Secure Maya Community; and Traveling Through the Land of the Eternal Spring: A Literary Journey. He’s producing a documentary set in Guatemala, Trouble in the Highlands. His wife and three children were born in Guatemala.Go to MillionMileWalker.com

or write the author at:

Mark@MillionMileWalker.comSixteenth annual SOLAS AWARDS

Winner Adventure Travel

Bronze Award:

Tschiffley’s Epic Equestrian Ride

by Mark Walkerbesttravelwriting.com/award-winners-2022

peacecorpsworldwide.org

Walker’s new book, “My Saddest Pleasures: 50 Years on the Road” will be available in May/June 2022.

Yalan utz, tata! Interesting life, reminds me somewhat of mine: Guatemala PCV trained by Basico in Costa Rica Fall of 1973, then working in San Andres Semetabaj, Solola with regional ag coop from 1974-1976, surviving brutal 4 February 1976 terremoto. Learned Mayan Kaqchikel to better communicate with indigenous farmers so extended original 2 year tour, then back home to California in March yet returning to Chapinlandia in April coordinating Christian work camps to aid with post- earthquake reconstruction plus medical teams. Met wife (student from Anderson University -Indiana- service team I coordinated) & married in 1977, directing Vacation Samaritans international service/medical ministries 7 years. Then served and raised family with Compassion International ministries in Dominican Republic & Hong Kong, then with Plan International in Colombia & Ecuador. Great service with numerous groups, spreading God’s footprints worldwide with many shortterm volunteers, paid staff and national leaders. Cuerpo de Paz provided my entryway to increased cross-cultural understanding and love for others just as they are worldwide.

Lorenzo–thanks for sharing. Yes, our lives had some parallel paths! And we were both with Plan in Colombia–now that’s another story which I tell in my first book, “Different Latitudes”. You might consider writing a book or some articles about your experiences and the importance of cross-cultural understanding and appreciation of others, no matter what language they speak!

Mark

Pingback: Million Mile Walker Dispatch, Launching My New Book: My Saddest Pleasures, May, 2022 – Million Mile Walker

The Revue magazine is an excellent and illustrative way of learning.

Unfortunately, I lost track of it. I only have the 2011 magazine.

Every year I take some English students to Antigua Guatemala, so they can practice with visitors from different countries.

Can you tell me how to obtain more of these magazines?

Thank you for your time and attention. Blessings.

Hi Luis — thanks for the kind words. The Revue is online only these days and you can find our current and back issues at https://www.revuemag.com/ – All the best