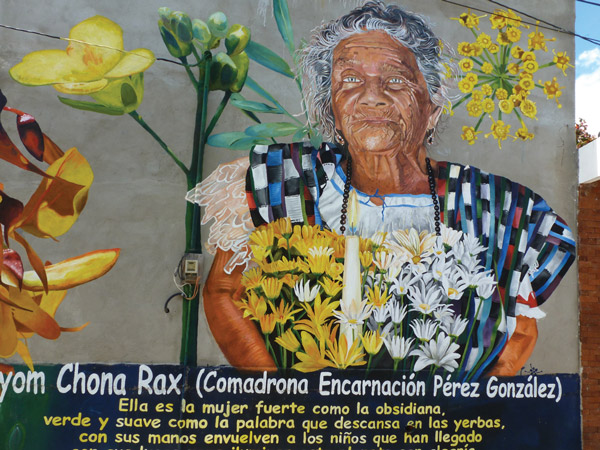

Labor of Love — Iyom Chona Rax

“I’ve delivered six generations of children. I didn’t count exactly but the number is around 2,000 babies.”

The towering portrait of midwife Doña Chona Rax near the Santiago dock in San Pedro La Laguna is remarkable not only for its artistic beauty, but also for the vitality and strength that radiate from its subject. Canal Cultural, the artist collective that executed the two-story mural, is committed to making art that affirms the Mayan culture and engages the viewer. I was definitely enchanted, going out of my way to visit the mural and to read the beautiful poem beneath it.

When I asked my Pedrano friends if they knew of her, they almost all said, “Si! She was the midwife at my birth—and at the birth of all of my brothers and sisters too!”

Doña Rax was sitting on her cement step when my translator and I found her. Like many Maya in San Pedro, Doña Rax speaks T’tzujil but not Spanish.

At 90, her posture is erect and shows no signs of frailty. Motioning for us to sit in plastic chairs, she perched on the single bed in a room bare except for a long row of cooking wood against the opposite wall.

“My friends call you grandmother,” I said.

“Yes, in 75 years I’ve delivered six generations of children. I didn’t count exactly but the number is around 2,000 babies. I worked here and also in San Juan, San Pablo and San Marcos.”

Much of this was long before tuk tuks, buses and roads. “I walked through the mountains. Sometimes I saw 15 women, giving prenatal care and delivering the babies. I worked day and night.”

She shook her head as if wondering at her own stamina. “I often had a headache,” she admitted.

“But how did you learn to do this? Were there other comadronas in your family?” I asked. Giving birth continues to be the leading cause of death of young women in the world.

“No, there was no one to teach me.” She explained, “I learned through my experiences. I married when I was 14. When I was 15—my baby was 6 months old—the midwife came to our house. She told my father she wanted me to stay with a woman who was in labor while she collected herbs the woman needed—there was no mercado for buying herbs then.

The midwife left me alone with the woman and was gone a long time and finally she was ready to give birth. I was not sure what to do. I prayed to God and delivered the baby but I did not know how to cut the cord. Then the midwife returned, and I learned by watching her cut the cord. That was my first birth.

“A few days afterwards another woman in labor came to our house saying she could not find a midwife. My father said both midwives were with women in other pueblos. He said maybe his daughter could help her.

“‘No, no, no,’ I begged my father, ‘I don’t want to go.’ I was scared. But my father said I should help her, there was no one else. And so I went.”

Doña Chona Rex’s reputation spread. “I had the women lie in bed instead of squatting to bring forth the baby,” she said. “Many women preferred this and asked for me.” I imagined that women also preferred her because of her sturdy competence and legendary devotion.

Doña Rex was emphatic that the woman’s husband be present for the birth. “Sometimes they would be afraid and try to leave! I would say they could not leave, they had to help and to watch what their wives go through in giving birth to a child.”

“In traditional Mayan medicine, healers, midwives and shamans are said to carry a don, a preordained calling to serve the community.”

“Yes, my father said that there were signs when I was a child that I had this don. He said when I was very young I had a favorite small knife. As I grew I favored a larger one. Then I treasured a pair of scissors. These tools, used to cut the umbilical cord, are by tradition the mark of a comadrona. He said my green eyes and curly hair were other signs, because they are unusual.”

Traditionally those born with a don are prohibited from charging for their services, but instead rely on donations. “Sometimes now, a man will give me 10 quetzales and say, ‘This is because you delivered my 10 children.’

Many people paid nothing or gave me 50 centavos. Sometimes they were very poor and I said, ‘Go right now with your little money and buy food for the mother.’ And sometimes the father beat his wife for having a girl because he believed that his wife was responsible for the gender of the child.”

“I kept working because I wanted to help. But now it’s been 75 years! Enough!” she concluded. Rising to show us out, she motioned at the two pregnant women waiting outside her door. “They still come for me,” she said, and invited them inside.

REVUE article: text and photos by Louise Wisechild

IN MEMORY

Doña Chona Rax (1924-2016)

This interview was conducted in Dec. 2014.

Doña Chona Rax passed away on Jan. 2, 2016.

Pingback: 5 Beautiful Murals in Villages of Lake Atitlan, Guatemala | Look! I'm a Pegasus!