In the Kingdom of Mescal

The Making of “In the Kingdom of Mescal: An Indian Fairy-Tale for Adults”

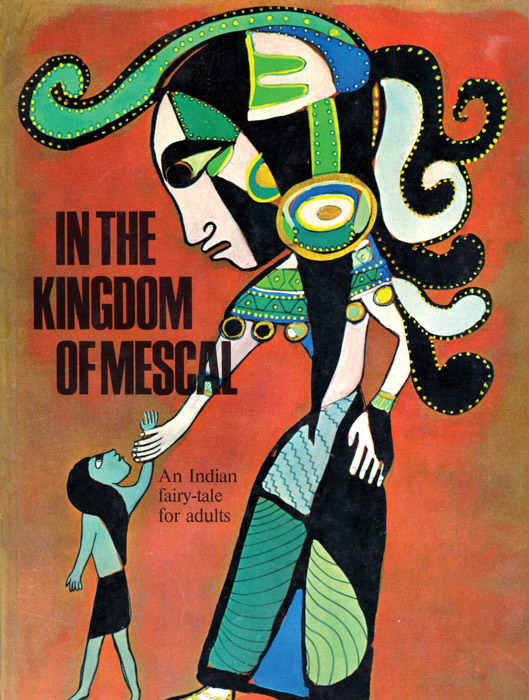

I discovered “In the Kingdom of Mescal: An Indian fairy-tale for adults” among items my parents had left me. A colorful, mystical figure holding the hand of a small boy dominated the front cover. On the inside cover was an inscription from my wife’s Guatemalan/German friends, who had given my parents the book when they visited Colorado at Christmastime in 1978. My wife’s friends knew the author, although his name was not listed anywhere. The book merely cited the publisher, Galeria Panajachel, Lake Atitlán, Guatemala; the year of publication, 1977; and the German printer. Enchanted by the tale, I did some research and soon identified the author as Georg Schafer, a German painter and poet, and the illustrator as Schafer’s Guatemalan-born wife, Nan Cuz.

Although “In the Kingdom of Mescal: An Indian fairy-tale for adults,” begins with “Once upon a time,” it is anything but traditional. The book is based on Guatemalan art and music collected by Schafer and the early memories of Cuz, who was born to a Maya woman. It is also strongly influenced by the psychedelic drug culture of the time.

The structure was inspired by another adult fairy tale, “The Little Prince,” by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, a poetic tale with the author’s watercolor illustrations. Unlike the little prince, who leaves his home with the help of a flock of migrating birds, the Indian boy, Blackhair, the young seeker at the heart of “In the Kingdom of Mescal,” uses a magic potion as the medium for transportation of the mind. Just as the prince visits other planets, each of which reveals a new story, so Blackhair embarks on a journey of revelation and gains a greater understanding of himself and the world around him.

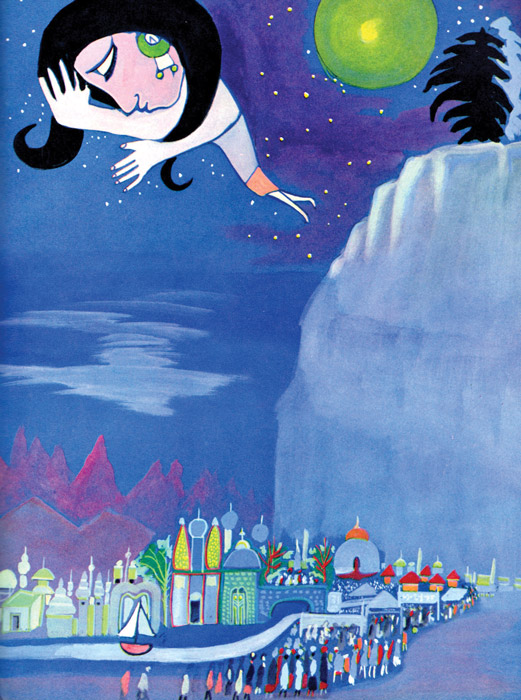

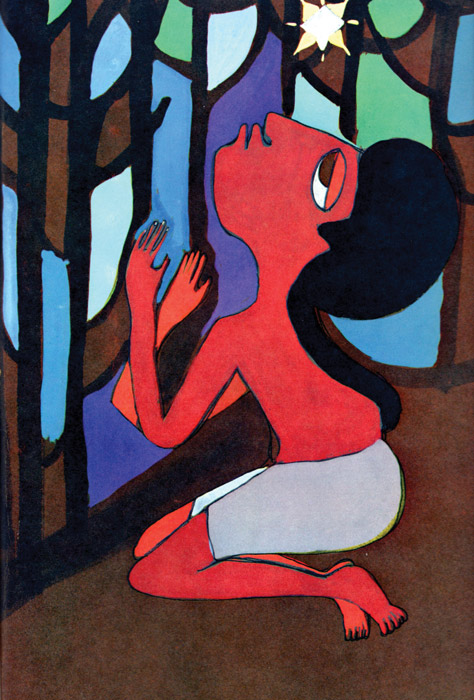

Blackhair desires to see beyond the surface of the world and gets his wish when a local medicine man gives him a potion that, when imbibed in a vast forest lit by a full moon, promises to take him to the Kingdom of Mescal, where all his queries will be answered. That night, Blackhair does as the medicine man advised, and as the landscape around him begins to dance, his fears dissolve, his feet grow massively large, and he vomits up a talking serpent. The snake identifies itself as Time and starts the boy on his quest.

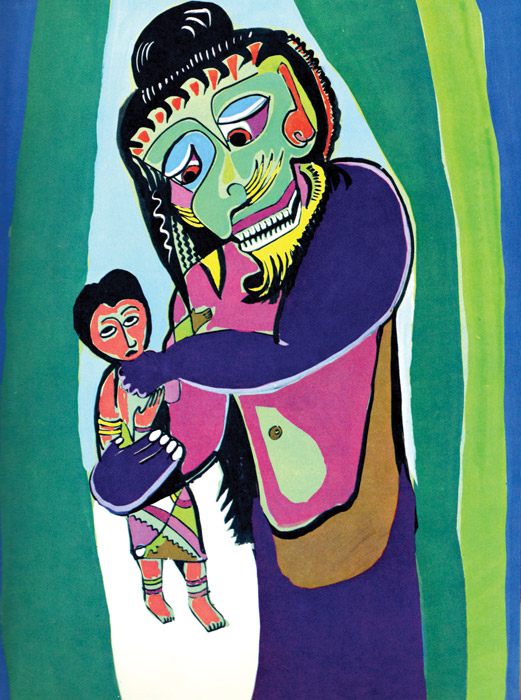

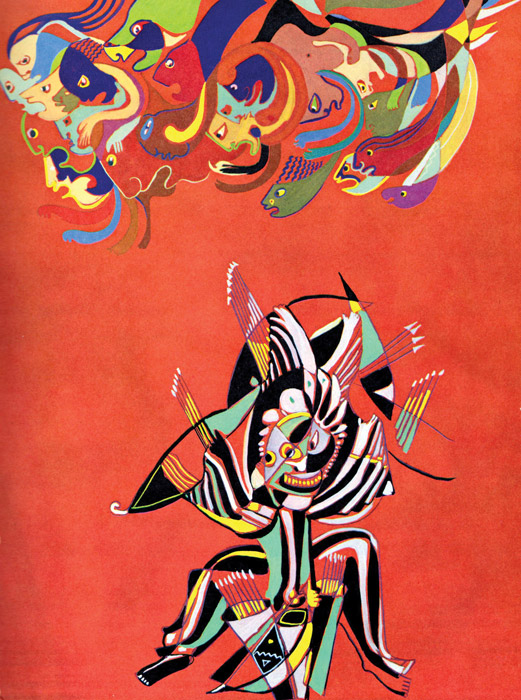

That quest involves a trip through the sky inside a raindrop, a malevolent emperor who rides a donkey with 100 legs, trees that bow and talk, a palace with 1,000 doors, and the awesome Lord of Mescal, who takes Blackhair on an interplanetary voyage before imparting some timeless wisdom. Along the way, Blackhair is stopped by a sharp-toothed, feathered giant who warns him that the journey through the kingdom of thoughts will be dangerous. The giant gives the boy a golden robe and says that his disloyal servants will try to lead him astray, but, if he escaped them, the Kingdom of Mescal would open before him. Blackhair continues his journey, encountering a series of perils, including a hissing, many-headed reptile. Blackhair survives, and the Lord of Mescal grants him the key to men’s hearts, which is loving-kindness and the clarity of mind that will help them find the right way. When he returns, Blackhair possesses nothing, but his people come to regard him as the richest of men and a great seer.

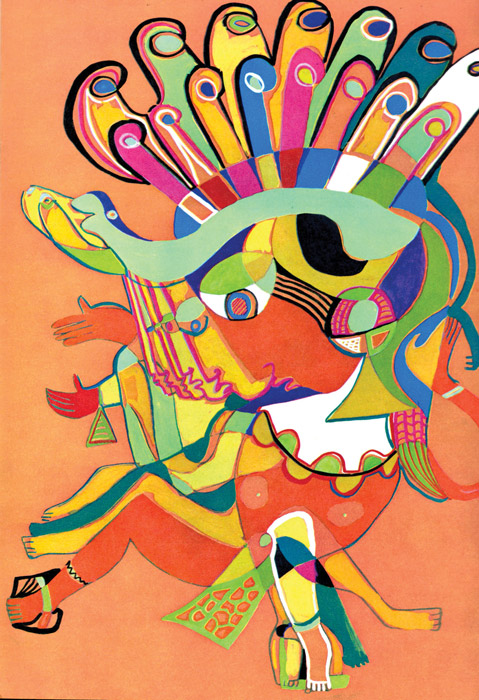

Schafer’s rendering of this supernatural tale, told in simple, unadorned language, makes little distinction between fantasy and reality. But it is Cuz’s colorful full-page illustrations, reminiscent of Maya art and weaving, that bring the book to life.

Besides being a writer, Schafer, who went by the name Oma Ziegenfuss, was an artist, visionary, mystic, philosopher and romanticist. During World War II, he distributed pamphlets for the Danish resistance but was captured by the Gestapo and sentenced to death for espionage. Himmler commuted his sentence to 15 years in prison, which Schafer spent in five concentration camps until the war ended. Around 1950, after working and studying at the Theological College at Fulda, he became a journalist for a newspaper in Hamburg, where he met Irmgard Cuz Heinemann, a photographer for the same newspaper. The couple married in 1952.

Heinemann, known as Nan Cuz (Cuz was her Q’eqchi’ Maya family name), was born in 1927 in the village of Secoyocte, in the municipality of Senahú, in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, to a Q’eqchi’ mother and a German father, a wealthy coffee plantation owner. Nan would be brought up under her grandmother’s supervision. Spanish was prohibited in the household of eight children, who spoke only their native Q’eqchi’. The Maya family structure is strictly matriarchal, and I couldn’t find a reference to Nan’s grandfather in my research, making her grandmother and mother the dominant influences in her upbringing.

The family lived in the north central part of Guatemala in a lush tropical forest where it rains up to nine feet per year. The diversity of plant and animal life is amazing: There are innumerable insects and colorful birds, including the quetzal, with its spectacular emerald-green and red plumage, as well as many different predators, such as jaguars and cougars. Their religion is based on a symbiosis with Roman Catholicism. Their view of the earth and the afterlife is reflected in ceremonial sites that can be found in caves like one I visited when leading a donor tour to the area. The cave got darker as I climbed down, until I reached an area of candles and copal, a tree sap used as incense. These caves are often described as entries into the watery Maya underworld. Life and death occur at middle zones between this world and the underworld, associating caves with both life and death.

Even at an early age, Nan carried images of this mystical, green world, and as an adult she would refer to her “mysterious talks with the rain forest” as well as “visions” she’d had while walking through the cornfields. She also believed that “Mother Earth provides everything but we treat her badly” and that one must ask Mother Earth’s permission to experience a true “feeling of oneness.” Her art reflects the deep and eternal connection between the earth, nature and all living beings. These myths, visions, colors, landscapes, animals and plants, buried deep in her psyche, emerged in her art and the illustrations of “In the Kingdom of Mescal.”

Nan’s village was in the center of a German settlement formed in the 1870s in Alta Vera Paz. It became the major source of timber and coffee for European markets. By the end of the 19th century, Germans owned 75 percent of the land, and a governor reported that peasants were fleeing from the landowners for whom they were forced to work. Nan said that her father, Hermann Heinemann, had “stolen” her mother, Filomena Cuz, from her village. He baptized his daughter with a combination of Germanic names—Irmgard Cuz Heinemann—that no one in the village could pronounce. They called her Nan Cuz.

Life on the German plantations was a far cry from what Nan would have been accustomed to in her village. The “Big House” of one of these plantations would have included innumerable bedrooms, a living room and a kitchen, with five or more kitchen helpers, and would have had electricity and drinkable water. A group of gardeners would have cut the grass and cultivated the exotic tropical flowers with nothing more than a machete. Hundreds of Maya workers worked on the plantation at any given time, cleaning the coffee plants or harvesting the beans. Then they processed and dried them on large drying courts, and, finally, cleaned and placed the coffee in large sacks to export to Europe. Some of the growers were said to have sent their shirts with the coffee down the Río Dulce, to the Caribbean, and all the way back to Germany, where the coffee would be sold and the shirts washed, pressed, and returned on the next trans-Atlantic ship returning to Guatemala.

By contrast, a Maya house like Nan’s was usually a good hike from the road. It had a thatch-roofed kitchen in the back and a wood-plank dwelling in the front with small, glassless windows, making for a relatively dark space inside. Sometimes up to eight family members would sleep in a small dwelling like this. Many people had a small altar with both Christian symbols like the cross and Maya symbols like an ear of corn, and the entire display was surrounded by candles. Firewood would be piled up on the front porch. Several coffee and fruit trees, such as bananas, would surround the home. The animals, including chickens and piglets, could be found behind the kitchen, which didn’t have a chimney, so the smoke from the fire would slowly drift up and out of the roof. Out in the back was a small round structure with a tiny opening, where one could enter to throw water on heated rocks for a steam bath.

Hermann Heinemann abandoned the family when Nan was young, but seven years later his second wife, who was German, traveled to Guatemala to take Nan to Germany, where she would receive a “good education.” Taking the same route as the plantation owners’ shirts, Nan hiked down to Panzós, which means “place of the green waters,” in reference to the Polochic River and swamps full of alligators and exotic birds. The river would eventually take her to Lake Izabal and down the Río Dulce, which is engulfed by a thick jungle filled with screeching monkeys and birds. The Dulce always reminded me of Joseph Conrad’s classic “Heart of Darkness.” Eventually Nan’s boat would arrive at Puerto Barrios, on the Caribbean, where she’d board a steamer bound for Europe with her new German mother. One can only imagine how a 7-year-old who spoke only Q’eqchi’ and had never worn shoes felt when she arrived in the Netherlands in the dead of winter and, eventually, Germany in the Nazi era. Nan learned German in order to gain the respect of her peers, although they taunted her for her small size and brown skin, calling her “little monkey.”

Nan’s mother agreed to her departure only on the condition that her daughter would be sent home after her schooling. But World War II broke out, and Nan didn’t see her mother again for 37 years. She called her stepmother Mena Cuz, or “Other Mother,” and found her very domineering. Her sense of guilt over not seeing her birth mother and losing contact for so long was profound, reflected in her so-called Madonna and Child paintings.

When the war ended, Nan was 18. Her father was a professional photographer and taught Nan the craft, although she preferred to paint. In 1950 she met and married Georg Schaefer. In 1971 they left Germany with their two children and settled in Guatemala, where they created La Galería de Nan Cuz, which would become the social, intellectual and artistic center of Panajachel.

The couple were early pioneers in the psychedelic movement and a part of the counterculture. They had both experimented with synthetic mescaline shortly after the war and published their findings in a scientific paper that led to correspondence with such luminaries as Albert Einstein. “Magic” drinks, including mescaline mixtures, had long been used in Native American societies as a means of spiritual transformation, expanding consciousness and opening the doors of the soul. Nan took mescaline “to enhance the images from my memories as a child and mysterious talks with the rain forest.” She also tried LSD, which, she said, didn’t agree with her. Above all, Nan’s deep and central connection with the earth, nature and living beings, learned as a child in the rain forests of Guatemala, would inform much of her worldview, and she expressed sadness at the way people abused the sacred Mother Earth.

Georg was a self-taught Buddhist and believed his art could serve as a visual guide to the deeper, intuitive self and would inspire “truth seekers.” According to his wife, he was “charismatic” and believed that his art and philosophy of life would guide others on a new path in life. Their book, “In the Kingdom of Mescal,” became known as the hippie bible, and Georg began to attract a group of people with similar views on life and formed a “clan,” which was to drive a wedge between the couple and eventually lead to their divorce. At 90, Nan is still in Panajachel.

“In the Kingdom of Mescal” is a psychedelic myth, as well as an exotic work of art rooted in Nan’s vision and her Maya culture. One edition of the book includes a foreword by Guatemalan writer and Nobel Prize winner Miguel Angel Asturias, who met Nan and Georg in Paris when Asturias was the Guatemalan ambassador to France.

Many more twists and turns remain to be explored. What was the impact of the Maya/German cultural mix on this tale? What other versions of the book are available? These are just a few of the mysteries that surround this fascinating “Indian Fairy-Tale for Adults.” But there can be no doubt that Nan and Georg’s unique perspective, as well as their experimentation with hallucinogenic drugs, bore rare fruit, and art and literature were richer for it.

RESEARCH FOR “THE MAKING OF THE KINGDOM OF MESCAL: AN INDIAN ADULT FAIRYTALE”

I researched the book for over four months and interacted various times with Nan Cuz’s son, Thomas Schaefer (“Galeria Panajachel”, Lake Atitlán). Thomas reviewed my initial draft and informed me that there was no “original (Maya) story” and that the book was inspired by the “Little Prince” by Saint-Exupery.The second key source was Dorothy Kethler’s article in the May, 2017 issue of the Revue, “A Journey to the Uncharted Depths of a Soul.” Dorothy objected to my reference to the use of mescal which she says Nan was “not happy about” and that Georg forced her to take it.

The research and use of psychedelic occurred prior to Georg and Nans return from Germany to Guatemala, and I modified the article to reflect that Georg used more drugs.

I also viewed a revealing documentary titled, “Nan Cuz, Painter-Burning Feather, Visionary Heart” directed by Anja Krug-Metziner. A German film team came to Panajachel to produce the film in 2008.

REVUE magazine article by Mark D. Walker.

About the Author (MillionMileWalker.com)

Mark’s passion for Guatemala started as a Peace Corps volunteer, followed by a career working for eight international organizations including MAP International, Make-A-Wish International and as the CEO of Hagar, which works with survivors of human trafficking.

According to Midwest Review, Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond “Is a story of one man’s physical and spiritual journey of self-discovery through Latin American, African, European and Asian topography, cuisine, politics, and history.”

Mark is a board member of “Partnering for Peace” and “Advance Guatemala.” He received the “Service-Above Self” award from Rotary International. His wife and three children were born in Guatemala.

A vast improvement on the earlier draft you sent me, Mark. Good job. Dorothy

Thanks for your input Dorothy. It was worth the research to get closer to the truth behind this fascinating tale–although some mysteries remain…

That book was such a treasure to find! Terrific review.

Windy,

Yes, it’s nice when a little gem falls in your lap every once in a while! Makes a writer’s life a lot easier–and more rewarding!

Cheers,

Mark

What a great article! I loved the illustrations as well. Really enjoyed this book review. Thanks, Mark!

Fascinating article!

Kerstin, Windy & Susan–so glad you all enjoyed it so much! the Revue did an incredible job including the awesome paintings!

Great story and review!! So glad I have a copy of the Revue Mag and I’ll check out some of the other resources too!

Hello Mark,

What an absolutely fabulous history your article unfolds. The personal stories of the creators of “In the Kingdom of Mescal” are so intriguing and complex. This seems just the start to a book! Thank you for your in depth research and clear writing!

Kristi

Kristi–thank you–I just saw your comment. I have another, very similar article in this month’s review, “Maya Gods & Monsters”–with similar spectacular graphics–check it out!

Nan Cuz passed on today. Both her art and her story are powerful. Although I got to know her through the research of this article, I never did meet her and would have liked to. Her worldview and artistry was informed both by her Mayan and German upbringing–an amazing combination.

Pingback: Guatemala: Trouble in the Highlands Mark D. Walker – Revue Magazine

Where can we see the documentary film? Would love to be able to watch it:

“… documentary titled, “Nan Cuz, Painter-Burning Feather, Visionary Heart” directed by Anja Krug-Metziner. A German film team came to Panajachel to produce the film in 2008.”

Correct spelling of the filmmaker’s name? (couldn’t find anything spelled Metziner):

“Anja Krug-Metzinger”

Filmproduktion GmbH

http://www.krug-metzinger.de/en/

Thanks for this most interesting article!

UPDATE: found the film, on Vimeo!

“Blazing Feather. Discerning Heart. – Nan Cuz. A German-Indian Painter” http://www.krug-metzinger.de/en/#produktionen

“In 1968, when her book “In the Kingdom of Mescal” assumed cult status within the hippie movement, German-Amerindian painter Nan Cuz was already a famous artist, having gained renown in the 1950s with her painting “The Madonna of Guatemala”. She was soon showing her work in exhibitions all over Europe and in the Guatemalan presidential palace.

An exceptional life story: Born in 1927 to a Mayan mother, at the age of seven she is forced to start her life anew in 1930s Berlin, the capital of the German Reich. Nan is now called by the name of Irmgard – and wears shoes. Her German father, who ran a coffee plantation Guatemala, works for the Reich Propaganda Ministry. She will go on to become a pioneer of the hippie era, exchanging ideas with Albert Hofmann, Hubert Fichte, Aldous Huxley and Albert Einstein. In 1971 Nan Cuz and her family emigrate to Guatemala, where she reconnects with her Native American roots. Despite being educated in Germany, Nan Cuz is able to rediscover her faith in the Mayan worship of Mother Earth.”

Blazing Feather. Discerning Heart. – Nan Cuz. A German-Indian Painter

Dokumentary film, 45 Min., Radio Bremen / ARTE 2008

Producer, director and screenwriter: A. Krug-Metzinger camera: Bernd Meiners sound: Jörg Johow editing: Elke Schloo music: André Feldhaus television editor: Thomas von Bötticher, Bremen / ARTE

DigiBeta / 45 |52 min. / 16:9 / German with English subtitles

Watch the film on Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/701861869