In Search of Almolonga

Church and plaza of San Miguel Escobar, facing west; probable vicinity of the second Santiago and possible site of its cathedral.

Exactly where was the center of old Santiago? Traditionally the honor has been assumed to belong to the urban center of Ciudad Vieja, the Old City. But was it?

Tropical storm Agatha raged throughout Guatemala in May, déjà vu of 9/11/1541 for the hard-hit area east of Ciudad Vieja. Weeks later, the church of San Miguel Escobar still sheltered people from some of the 80-plus homes that were lost along the river that cuts through a crevice on the skirts of Volcano Agua. Logs and limbs dumped by the water had been collected and piled in front of the church. Front loaders still scooped up all sorts of debris left by the storm.

Residents there, keen on their history, readily relate the story of that night 469 years ago when a similar storm rained torrents of water, dislodging boulders, uprooting trees and tearing down walls. Some go as far as to say there has not been a storm so severe until Agatha.

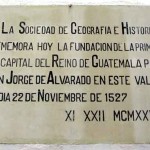

There were no front loaders in 1541 to clean up Santiago, the name of the second location of the seat of the Spanish government in Guatemala, located in the Valley of Almolonga, currently Ciudad Vieja and San Miguel Escobar. The destruction resulted in moving the town in short order to what is now La Antigua Guatemala. But exactly where was the center of old Santiago? Traditionally the honor has been assumed to belong to the urban center of Ciudad Vieja, the Old City. But was it?

According to historian J. Joaquín Pardo, “..analysis of colonial chronists and 20th century excavations and research show that is not so.” The chronists would seem to be the first source of information, and János de Szécsy read them, although with a grain of salt. “The history of Santiago was only of modest interest for the chronists, who concentrated their attention on the detailed history of Antigua,” he wrote in Santiago de los Caballeros de Goathemala en Almolonga. Szécsy carried out extensive excavations in 1950 and concluded, “There exists no convincing proof to suppose that the capital was in Ciudad Vieja.”

Official records of the town council of that early settlement, printed in Libro Viejo, include a plot of the city and names of its inhabitants. Having reached a severe state of deterioration, the originals were finally compiled as best they could be, laminated in 1968 by the U.S. Government Printing Office and remain in Washington. Analysis of those records by the Academia de Geografía e Historia concludes that Santiago “can be positioned to the east of the urban center of Ciudad Vieja, as far as San Miguel Escobar.” Pardo recognized, “Thanks to the scientific works, the limits and center of the second Santiago are known with almost complete certainty and exactitude.”

Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado had set out from Mexico in 1524 to extend the conquest of Spain to Guatemala. The contingent, basically an army, stayed but a few months in Iximché, the first place named Santiago, but then moved on. After a brief stay in Comalapa, they reached the Valley of Almolonga, a pre-Colombian settlement long since abandoned, and said, ‘This is good. Let’s stay awhile.” It was beautiful, with fertile land, trees to provide plenty of fruit and wood, pastures and moderate temperatures. Volcanoes provided protective ‘walls’ for defense as well as ways for easy in-out. Almolonga means “gushing waters,” one of the major pluses but also “a prophetic touch to the catastrophe that awaited.” (Libro Viejo)

“The ‘city’ was itinerant for more than two years. All the neighbors and members of the council were soldiers, so the ‘city’ was established in the military camp,” wrote Jorge Luján Muñoz in Historia General de Guatemala. In 1525 it became the first chore of the council to decide whether to settle in Almolonga or choose another site. They explored the area and debated. The few objections included wind, marshes and “the earth shakes a lot because of fire that the volcanoes put out,” but in the end it was almost unanimous: they would stay.

“What is said to be the palace of Alvarado turned out to be the façade of the monastery. None of the three monuments of Ciudad Vieja were found to be authentic.” Szécsy attributes the claims to ‘local legend’.

Officially founded on November 22, 1527, the second Santiago was lined out and parcels of land assigned “according to the custom established in the foundation of Spanish cities in other parts of New Spain,” wrote Christopher H. Lutz in Historia Sociodemográfica de Santiago de Guatemala. Libro Viejo records a church, public plaza, hospital and lots for civil authorities and neighbors. More than 600 indigenous people were established outside the grid, where they grew vegetables and cared for the cattle of the Spanish.

The Santiago built over the next 14 years was not elegant. The 100-or-so Spanish were people of simple preference, “of low nobility and poor in Spain,” wrote Szécsy. “I suppose Santiago was something like a beautiful 20th century village.” There were no architects or specialized workers, and no large buildings, given the size of excavated foundations.

The Franciscan and Dominican orders established monasteries at the corners of the city, the Mercedarians closer to the cathedral. And, of course, there was the palace of Pedro de Alvarado, whose wife, Beatriz de la Cueva, died in the storm of 1541 along with half the population.

The Franciscans stayed in Santiago after the move to care for the population that chose to remain there after the catastrophe, basically indigenous Mexicans who had come with the conquistadors. The area was slowly repopulated, building over the structures of Santiago. According to historian Fuentes y Guzmán in Ciudad Vieja, “The Franciscan church became parish church of the new municipality.” These inhabitants adopted the name of Ciudad Vieja.

Ruins of the Santiago cathedral, the palace of Alvarado and the chapel of Doña Beatriz have been said to lie under that church and its plaza, the basis for claiming the now urban center of Ciudad Vieja as the urban center of Santiago. But studies of measurements, orientation, architectural style, geography and observation of flood patterns over the centuries fail to support the claims. According to Szécsy, “What is said to be the palace of Alvarado turned out to be the…façade of the monastery,” adding, “None of the three monuments of Ciudad Vieja were found to be authentic.” He attributes the claims to ‘local legend’.

Unfortunately Szécsy’s studies were suspended due to lack of funds. “The foundations of the majority of public buildings, like the cathedral, the Mercederian monastery and the Royal House probably would be discovered if more excavations were done.” The Palace of Alvarado, the Dominican monastery and perhaps even the center of Santiago are believed to be buried now somewhere under private coffee farms. “It is logical to suppose that the city founded in 1527 was on the site of San Miguel,” wrote Lutz.

San Miguel Escobar includes coffee farms and is in fact a neighborhood within Ciudad Vieja, so the claim of that municipality is technically correct. The hitch is location of the urban center and identification of the ruins.

Today the ruin said to be the chapel where Doña Beatriz and 11 ladies of her court died on the night of the storm is bordered by school classrooms, where very much alive children play, 469 years later. Life goes on, with or without answers about the past.

photos by Jack Houston

Thank you, Joy, for the beautiful story.