Emerald Lightning

Exploring the Cloud Forest Realm of the Resplendent Quetzal-Serpent

text and photographs by Thor Janson

It has been five days since I last saw the sun in my quest to observe and photograph the resplendent quetzal. Now I really know why they call this cloud forest! I’m up near the ridge of the Sierra Yalihux in the mountains of Alta Verapaz at an elevation of 7,000 feet. A bank of clouds has settled around the mountaintop and doesn’t want to leave.

Sitting by the open fire in the middle of our little hut this evening, I give thanks that I am in here, cozily writing, instead of outside in a dank tent. Our host, whose name is Rosendo Chun Pop, is a Kek’chi Indian.

Since he has no knowledge of Spanish and I have only the most rudimentary understanding of his Mayan dialect, our communication is limited to gestures and smiles. But, as we sit sipping sweet coffee, he seems happy to share his little cabin and warming fire with us and his smiles and twinkling eyes convey his friendliness better than words ever could.

The temperature outside is probably around 45° Fahrenheit, but the wet-cold of the clouds makes it feel like it is below freezing. I am here in the mountains of Verapaz with naturalist Verónica Chavajay, a 34-year-old Guatemalan native from Santa Clara La Laguna in Sololá province, a town perched above the sacred waters of Lake Atitlán.

Her ancestry includes both Mayan and Spanish elements. From an early age she has pursued an avid interest in studying nature and bush medicine; we share an interest in studying the quetzal in its natural habitat.

A Capital Offense

Although ornithologists have hailed the quetzal as the most spectacular bird in the Americas, few people, outside of the natives who live in the highland forests by death they who killed the bird with the rich plumes because it was not found in other places and these feathers were of great value because they used them as money.”

The Maya had a symbolic system of colors: black for weapons, obsidian; yellow for food, corn; red for war; and blue for sacrifice. But the royal color was green, the color of Kukul —the serpent bird.

Highland Indians were allowed to trap the birds and remove their tail feathers (which grow back each year) but they were forbidden to kill or keep them captive. After by death they who killed the bird with the rich plumes because it was not found in other places and these feathers were of great value because they used them as money.”

The Maya had a symbolic system of colors: black for weapons, obsidian; yellow for food, corn; red for war; and blue for sacrifice. But the royal color was green, the color of Kukul —the serpent bird.

Highland Indians were allowed to trap the birds and remove their tail feathers (which grow back each year) but they were forbidden to kill or keep them captive. After the cacao bean, which was used as a form of currency, the commodity that probably contributed most to the native’s wealth were these feathers.

When the great Mayan cities fell the highlanders continued to trade quetzal feathers with the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, where Mexico City now stands. When the Spanish conquistadors visited the Aztec city they found rulers, priests and dignitaries wearing elaborate headdresses made from quetzal feathers.

Bernal Díaz, who chronicled the conquest of “New Spain,” described how the great Montezuma, when he came to meet Cortés, was shaded by a huge canopy of quetzal feathers. But Montezuma made a fatal error. According to ancient texts left by the Mexica, Quetzalcoatl, man or god, had promised to return from the East in the year 1-reed (1519), and this was 1-reed.

Assuming that the Spanish who landed on the coast of Veracruz were the returning gods, the Aztec emperor failed to prepare a defense. Before he knew what had happened, Cortés and his mangy army of 400 had defeated and sacked Tenochtitlán. And along with plundered gold, silver and gems,

sent back to the courts of Europe were the exquisite plumes of the quetzal.

Before long there was a growing demand for the feathers. No longer would the serpent bird be protected. The new rulers declared them to be free game.

By the 16th Century central Europe had been largely deforested and the Spanish found a ready market for fine tropical hardwoods. And so they began a process of desertification that continues today.

Chun’s Place At Last

On the other side of the Motagua Valley a series of switchbacks took us up into the mountains of Verapaz.

Gradually, the sweltering desert gave way to pine forest and then a cool evergreen broad-leaf forest. An hour later we stopped in the little town of Tactic and had lunch at a restaurant called Comedor Bombil Pec, where a beautiful young Mayan girl served us bowls of the regional specialty Kak’ik, a rich turkey and chile stew accompanied by fresh roasted corn tamalitos.

After a short siesta we headed out in our Jeep down a badly rutted track, which led us into the Polochic Valley along the rushing river. Down and down we went. After hours of constant pounding we arrived at the village of Tamahú, on the floor of the valley. Here we took a right turn onto an even more rustic roadway that led up into the coffee plantations. It was hot and steamy. The vegetation was very lush with many palms and a profusion of epiphytes.

We observed many beautiful birds: keel-billed toucans, flocks of little green parrots and several colonies of oropendola, easily identifiable by their strange nests which look like miniature hammocks hanging high up in huge kapok trees.

It took us another four hours to climb up through new and abandoned cornfields and get to the forest edge. The misting rain, called cheepy-cheepy by the natives, had begun and it was getting cold. I was happy that we were nearing our destination.

Entering the cloud forest was like stepping into a vast cathedral bathed in perpetual twilight. And as soon as I had entered I felt that there was something unusual about it. Something that seemed very ancient and mysterious. Huge old oaks and alders towered up to form a canopy 150 feet above us. These massive trees were covered with a profusion of mosses in which were rooted ferns, herbs, shrubs and even small trees along with countless species of orchids, bromeliads, epiphytes and vines.

Everywhere there were giant tree ferns, many growing to more than 40 feet in height. More than a century ago the English naturalist William R. Brigham saw these forests and wrote:

“Tropical vegetation cannot well be described. The real trouble that meets the novice on the threshold of the tropics is the utter inadequacy of the English language to express the variety and luxuriance he sees in the vegetable world. Even in color his vocabulary fails him and he must include in the name of ‘green’ so many distinct tints that he often fails to try.”

It was very silent. Through the mist the only sounds that we could hear were made by water. Gurgling streams and rivulets and drops, cascading down from one leaf to another. We continued to slog up the muddy trail and it was a surprise when, after what seemed like a very short time, we came to a clearing where there stood a little thatched-roof cottage out of which arose a plume of blue smoke. Rosendo Chun’s place!

He was not home but his two daughters came out to greet us with steaming mugs of hot coffee. I used the rest of the daylight to try to locate a quetzal with no luck. It was raining steadily and all the forest creatures were staying inside their warm nests and burrows.

When I got back I found that Rosendo had returned from hunting and had prepared slabs of wood at one end of the cabin, which were to serve as our sleeping quarters. He greeted me by saying “hass capey?” which Veronica told me means “do you want something to eat?”

I replied “oos,” which means “good, affirmative.” Soon we were served hot stacks of yellow and blue corn tortillas along with a bowl of cooked green herbs called “makui,” which tasted like spinach. It was a simple meal, but one that tasted good enough for a king, especially after the day’s exertion.

I tried to ask Rosendo about the quetzal. “Rochoch Li Quetzal?” I asked, reading from the list of phrases I had in my notebook. This was supposed to mean “quetzal nest” but Rosendo just sat there smiling and nodding at me.

His whole family—wife, three daughters and two sons—was sitting around the fire watching with wide-eyed curiosity. Each time I tried to say something in Kek’chi they all burst out laughing and mimicking my pronunciation in high-pitched squeals. They laughed until they cried as if this strange alien visitor trying to speak their language was the funniest thing they had ever seen.

It was then our turn. Verónica picked up different articles giving their Spanish or English name and our host and his family would attempt to repeat the words. This only caused more uproarious laughter by everyone. In this way we passed our first evening together.

We spent the next few days getting to know the area and looking for signs of the quetzal: fruiting trees where they might be found eating and potential nest sights. One afternoon while I was trying to get a photograph of an unusually large red snail, Rosendo’s youngest son Chung came by and seemed fascinated that I was giving the snail so much attention. I looked at him, then pointed to the snail and smiled, nodding.

There Was No Escape

When I was finished photographing, the boy picked up the eight-inch long snail and put it in his pocket. He gave me a big smile, nodded, and pranced away into the forest. I went about my business, thinking nothing about the incident, except that it was nice that these people were so friendly.

Later that evening at dinner we were brought our stacks of tortillas as usual, but when I got my stew bowl I immediately noticed a strange smell and saw strips of something weird in the broth.

Then I noticed an antenna. Oh no! Chung had assumed that my interest in the snails had gastronomic implications and collected as many as he could for our dinner. The whole family sat there smiling at us. There was no escape.

It was a beautiful gesture on his part but I must admit that the slimy, half-cooked snails were among the hardest things I have ever had to eat … right up there with raw sea urchin and fermented whale blubber. But we had to smile and eat it. Anything else would have been an insult.

From then on if I was studying some spider or worm and heard one of the family coming, I would quickly divert my gaze to the trees and hope that they would not discover my true focus of interest. Nevertheless, we were treated to a variety of strange fare including wild pheasant, giant tree maggots, and smoked monkey, which, by the way, was not half bad.

Sounds Like Quetzals

One morning I awoke before dawn. Still in a dreamy state, I could hear faint but distinct calls coming from all sides. It was a sad, slow sort of cooing. I thought it must have been Rosendo’s turkeys digging around for insects and worms outside the cabin. I woke up Verónica to ask her what she thought.

“I can’t be sure,” she said, “but it sounds like quetzals.”

Adrenaline shot into my blood and I was up and dressed in an instant. In the past I had heard one or sometimes two quetzals singing while exploring the forest, but this sounded like several dozen. We went outside in the darkness. It was windy and I was startled to find the sky absolutely clear and full of the brightest stars I had ever seen.

The calling continued; some of the birds were very near while others seemed to be calling from across the valley. We stood listening until the first brilliant rays of sunlight came over the horizon. It looked like it would be a bright, clear, sunny day, a rare enough event in the cloud forest. Rosendo’s youngest daughter brought us hot coffee and we stood at the edge of the clearing surveying the forest above and below.

Over the next few minutes the cooing diminished to almost nothing. Our next move would be to go out in search of whatever had been making the sound. Suddenly, as the first beams of the sun began to touch the canopy—a spectacular sight!

Without any warning a form, a bolt of shimmering emerald green, shot vertically up from the forest. It was a large male quetzal spiraling upward with long tail feathers streaming behind. As he continued his skyward flight he made a loud, raucous cry: WAKA WAKA WAKA WAKA.

He continued swimming up through the air until he was several hundred yards above the forest, after which he dove, with wings held close to his body, streaking into the canopy on the other side of the valley.

I could hear my heart pounding in my chest. This was nothing like I had ever seen or read about. Not just the amazing display flight, but the loud, almost macaw-like cry that the quetzal had made.

Then another quetzal shot up out of the trees in vertical flight. Over and over again this expression of sheer exuberance, joy and freedom was repeated. It occurred to me that no other creature I had ever seen so embodied the symbol of the phoenix of Egyptian mythology; rising immortal from out of the ashes of destruction.

Rosendo came down to where we were standing. “Li Kukul,” he said smiling and pointing to the forest below. We nodded!

Blood Of The Dead

Standing there I wondered whether old Rosendo had any idea of the role the quetzal had played in the history of his people. According to tradition, the quetzal took part in the struggle between Spanish conqueror Pedro de Alvarado and the great Mayan Chief Tecún Umán.

After Alvarado’s mercenaries had slain 30,000 Maya on the battlefield near Xelajú (Quetzaltenango) innumerable quetzals flew down to earth and settled on the bodies of the warriors. All through the night, keeping deathwatch, the quetzals covered the bodies of the slaughtered Indians.

At dawn the birds flew into the sky again, but different than before: Their breasts had soaked up the blood of the dead, and since that day the quetzal has been red underneath.

Later that morning I was writing up some notes and I decided to try and sketch what the quetzal’s display flight had looked like, knowing that getting good photographs of it would be next to impossible.

As I looked at my drawing it dawned on me that the figure of the quetzal, flying straight up into the sky with tail feathers rippling behind, looked oddly reminiscent of the Greek caduceus: two serpents intertwined about a staff and topped with a winged sun; carried by the ancient messengers of the gods, Mercury and Hermes.

Could it be that the winged serpent of the Maya and the Egyptian symbology, which gave rise to the caduceus of Greek mythology, had a common origin? Both represented the herald of the forces of light, the Life Force. Thousands of years before the flowering of Egyptian civilization, the great sages of India had used essentially this same symbol. It stood for the serpentine power of life-energy that they termed “Kundalini” in the ancient Vedic scripture.

We spent three months living with Rosendo in the cloud forest. We logged hundreds of hours observing the quetzal’s courting, nesting, eating and rearing their young. I was able to take many photographs, which have been used in campaigns to promote the conservation of this supremely beautiful bird.

In-flight Meals

Quetzals are sedate birds who perch tranquilly for long periods. Their flight is undulating with intermittent bursts of rapid wing beats. Food is chiefly fruits, especially of the Laurel family (Lauraceae), and occasionally insects, both of which are plucked from stems or foliage in mid-flight at the end of a sudden upward or outward sally, without alighting. It is an unusual behavioral trait that the quetzal seems incapable of taking a fruit while perched.

I have spent many hours observing quetzals feeding in fruit trees and have noticed that even if the bird is perched on a branch full of fruit, and even if the fruit is within inches of its beak, it is unable to take it. Only in flight will the bird pluck the fruit. Sometimes a lizard, frog or snail is taken.

The song is simple but often very melodious, the most common being a melancholy coo-cool, coo-cool. Sometimes the male can be heard singing an unusually beautiful song of deep, smooth, slurred notes in simple patterns: keow kowee keow k’loo keow k’loo keeloo. On a few occasions I have heard them make sounds remarkably similar to a cat’s meow.

Ritualized reproductive behavior begins in March or April. Often male and female quetzals can be seen flying through the forest in small flocks, and it is at this time of year when the male’s spectacular vertical display flight is most often seen.

Once the male-female pair is formed they proceed immediately to search for a nesting site. Often pairs will attempt to return to nests used the previous year and intense competition between pairs can ensue.

The male, especially, can be seen making aggressive spiraling flights and calling loudly if any other pair is seen near his chosen nest, though I have never seen actual physical combat.

Since quetzals, because of their relatively weak beaks, are only capable of carving nest holes in the most rotten tree trunks, there are probably cases where some pairs are unable to mate because of an insufficient number of nesting sites.

Once a good site is found—and it may be either in the middle of the forest or an adjacent clearing—both male and female go to work making the hole, usually from 5 to 27 meters (16 to 90 feet) above ground. The hole is deep and similar to that of a woodpecker. In fact, sometimes quetzals will take over an abandoned woodpecker nest.

Two pale blue eggs, which measure approximately 30 x 35mm, are deposited on the floor of the unlined hole. Both the male and female take turns with the work of incubation, which takes 17 or 18 days.

When the nestlings hatch they are perfectly naked with pink skin and closed eyes. Now the parents spend their days bringing food that consists at first primarily of insects and other small invertebrates. After 10 days or so their diet is enlarged to include a wide variety of larvae, small frogs, lizards, snails and fruits.

After three weeks the chicks are fully feathered and ready to leave the nest, although often they will remain in the nest for another week or so. As soon as they leave the nest the chicks disappear with their parents into the densest part of the forest, which affords the safest refuge.

During nesting the quetzals are threatened by a variety of predators, including weasels, coatamundis, hawks and eagles.

There is a popular myth that the quetzal nest is always equipped with two holes so that the male does not damage his tail feathers entering and leaving. In truth, the nest usually has one entrance, and the male does often damage his tail coming in and out. Fortunately, the beautiful tail feathers grow back.

It is also a myth that the quetzal cannot be kept in captivity. Many zoos around the world have maintained quetzals in their collections, though to date only one successful breeding in captivity has been reported.

The Most Spectacular Trogon

The quetzal is the most spectacular member of the Trogonidae family of birds. The Trogons are comprised of 39 species and are best represented in the Americas, where they inhabit nearly all wooded areas of the continental tropics and even range beyond to southern Arizona (USA), Cuba and Hispaniola. The remaining members are found in Africa and Asia.

Since Trogons are non-migratory and move but little locally, the existence of three widely separated populations (American, Asian and African) is cited by scientists as further evidence that the Earth’s continents were once united in one super-continent.

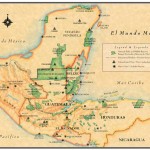

Also, in past geological ages, when tropical forests extended far beyond their present limits, the ancestors of today’s Trogons probably were much more numerous with a wider distribution. The present-day quetzal ranges from the mountains of the Mexican state of Chiapas to Western Panama. There are two subspecies separated by the lowlands that exist in central and southern Nicaragua.

Trogons exhibit similar behavior and physical structure: They are arboreal birds of medium size with compact bodies, short necks, short stout bills and short legs. The plumage is unusually soft and delicate.

All males exhibit glittering green, blue or violet upper plumage while the breast is a contrasting red, yellow or orange. Females have a more muted coloration dominated by tones of brown, gray or slate.

Since first being described in literature in 1830, the quetzal has been assigned at least 10 different names including: Trogon pavoninus, Trogon resplendens, Calurus resplendens, Caluras paradiseus and Pharomacrus paradiseus.

Today scientists identify the quetzal with the name Pharomacrus Mocinno. In Latin, Pharo means “light” and Macrus means “big:” bird of big light. Mocinno is the family name of the European naturalist who first obtained study skins of the quetzal. Mocinno was successful in shooting numerous examples and sending them back to Old World academies, which in turn honored him by immortalizing his name.

A Legend In Peril

Most of us are aware that the quetzal is an endangered species. But if the quetzal is just one of perhaps 30 million species on the planet, why would its disappearance be of any great importance? How could this negatively impact humanity and nature?

If the quetzal, one of the most beautiful creatures on Earth, becomes extinct, it will be because we allowed humans to destroy them. Knowing that we are accountable, regardless of the fact that it is one species among many, will be the cause of lasting dishonor and sadness for the human family.

The decline of the quetzal is not an isolated occurrence. It is just one example of what is happening in general to nearly all natural-life systems around the world. The quetzal is in decline because forests where they live are being destroyed. Already more than 80% of the original forests have been eliminated.

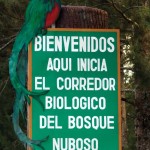

There is small relief in the fact that there are more than 50 cloud forest reserves in Mesoamerica that protect the resplendent quetzal’s habitat.

These range from small, private reserve projects such as the one established at Chelemha in Alta Verapaz in Guatemala, to the huge, magnificent El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve in Chiapas, Mexico. Every country in Central America has its own cloud forest protected areas and they are all worthy of a visit.

We hope to preserve enough cloud forest habitat in Central America to ensure that the quetzal may continue to be the living, legendary symbol of freedom.

(I have no website.) Thank you so much for this presentation.

I used to live in Guatemala in the late ’70’s. I have been returning to Montellano for our fifty bed clinic. I got to go to Xejaju’ to see a child for whom we had surgery.

I do so hope we can keep the beloved Quetzal alive. I hope people will realize he is a magnificent creation. When I an in Antigua I always get two copies of Revue in case there is something on both sides of the page that I want to save. I have several photo albums of the work we have done in Montellano. (Clinica Ezell)

Again, thank you. Keep the banner flowing to preserve the rain forests.