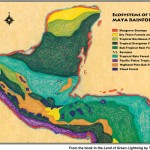

Ecosystems of the Mayan Rain Forest

An incredible diversity of life exists in the Mayan Rain Forest, the biological crossroads of the Americas

For centuries the land of the Mayan rain forest has been of particular interest to biologists because of its unique location. It is at the crossroads of two of Earth’s major life zones: the Nearctic Realm (North America) and the Neotropical Realm (South America). It is here in the bio-geographical heart of the continent where many neotropical plants and animal species reach their northern limits of distribution, while large numbers of Nearctic genera and species reach their southern range of dispersal. Maples and oaks grow alongside mahoganies and zapotes; coyotes and mountain lions share the forest with olingos, howler monkeys and jaguars.

Over vast periods of time, including at least four ice ages, major migrations of both plants and animals occurred across the narrow isthmus. As glacial ice melted, the oceans rose, inundating much of Central America.

Many species became isolated on mountaintops that had become islands. Today the ancient tropical highland forests are home to large numbers of unique species and have the highest rate of endemism.

The exceedingly varied types of soil and topography, ranging from the ancient Cuchumatanes Mountains to relatively youthful volcanic areas, combined with marked altitudinal and climatic variations, from hot deserts to cold alpine regions, have given Guatemala the richest flora in all of Central America with an estimated 8,000 species of vascular plants. Of this number many are unique species confined to particular canyons and volcanos. Tropical rain forests are located in a belt around the planet between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, the main limiting factor being temperature. Rain forests cannot exist where average temperature falls below 20 degrees centigrade (68°F). This temperature boundary is related to both latitude and altitude. Ecological zones occur because as altitude increases, temperature decreases, resulting in climatic conditions favoring different plant communities. The rain forest boundary is reached at about 3,000 feet above sea level. At this elevation, there is a gradual transition into montane broad-leaf forest and, higher up, mixed pine-oak forest. Along windswept mountain ridges the nearly permanent cold fog favors a ghostly pygmy forest where the trees are small and scraggly, covered with a profusion of orchids, bromeliads and other epiphytes.

At the crossroads of two of Earth’s major life zones, maples and oaks grow alongside mahoganies and zapotes; coyotes and mountain lions share the forest with olingos, howler monkeys and jaguars.

If we made an expedition from Guatemala’s Sipacate beach and followed a straight line northeast up to the Río Lagartos Special Biosphere Reserve on the north coast of the Yucatán Peninsula, we would pass through some 20 distinct life zones.

Let’s begin our journey on the wickedly hot black sands of the Pacific shore with a profusion of sea birds and the nesting ground for endangered sea turtles. From the coast we would go through the mangrove swamps. These dense, bug-infested forests provide nesting grounds for many bird species, nurseries for fish and shelter for a wide variety of animals. Around every bend we feel the presence of the master of the ambush. Crouching hidden in the tall grass, cruising undetected just beneath the grey gossamer hull of my kayak, the gaping maw of the giant leviathan Crocodylus acutus (American crocodile).

Next we cross a wide belt of high coastal forest, where huge trees reach up toward the sun, trunks whitened with lichens and covered with vines, making them very difficult to identify. Within the forest large “islands” or savannas, typified by coarse sandy soil, support a variety of grasses, bushy plants and small stands of slash pine. From here we ascend up through a transitional zone called “bocacosta,” featuring ferns, palms and large trees covered with vines.

Up we go into the mountains, scaling the 13,000-foot peak of Tajumulco volcano, the highest point in Central America. Here mist-enshrouded cloud forests and pine forests predominate.

Now on through the central Highlands and a series of inland plateaus and valleys, where pronounced wet and dry seasons and moderate temperatures favor forests of pine, juniper and cypress and a profusion of flowering herbaceous plants.

The alpine habitats of the Cuchumatanes is where we encounter cold pine forests and enchanting meadows of tussock grass, succulents and giant agaves. From here we begin a gradual descent into the vast lowland forests of the Yucatán. Our route takes us throughout three biosphere reserves: Montes Azules, Mayan and Calakmul.

As we move northward, rainfall diminishes and forests become dryer and less exuberant.

Approaching the end of our expedition, we pass through wide belts of deciduous and dry thorn forests which are desert-like, hot and arid.

From here to the northern coast, once again we find ourselves in hot mangrove swamps, the foraging ground for thousands of pink flamingos.

Finally, we reach the sand dunes and the blue waters of the Caribbean Sea. We are ready to take a dip in the ocean and paddle out to the coral reef. The reef itself is the result of tiny animals related to jellyfish building little shelters of calcium carbonate, one on top of another. After millions of years, these structures have become what is today a magnificent reef. The reef ecosystem is in many ways the marine equivalent to the rain forest; both are considered the Earth’s most productive life systems. The reef teems with its seemingly endless array of tiny, brightly hued tropical fish, squadrons of fierce-looking barracuda, meandering parrot fish and groupers, hair-raising hammerhead sharks and an occasional gentle manatee.

We end our journey standing on the sands of the Yucatán, gazing out at the ocean, the red sun looking as though it is melting into a molten sea of gold.

- The Highlands of San Marcos include a mixture of trees including pine, oak and liquid amber.

- The author at work in his office